A Story That Begins in Silence

At 15, Maya had done everything right. She excelled in school, played competitive tennis, and had begun developing breasts at 11, like many of her peers. Yet as conversations among friends turned toward “first periods,” Maya grew quiet. Months turned into years. There was no bleeding, no cramps, no menstrual cycle.

Her pediatrician reassured her at first: “It may just be late.” But by her sixteenth birthday, the silence of her uterus became clinically significant.

Primary amenorrhea is often first encountered not in laboratories or textbooks—but in quiet clinical rooms where adolescence does not unfold as expected.

What Is Primary Amenorrhea?

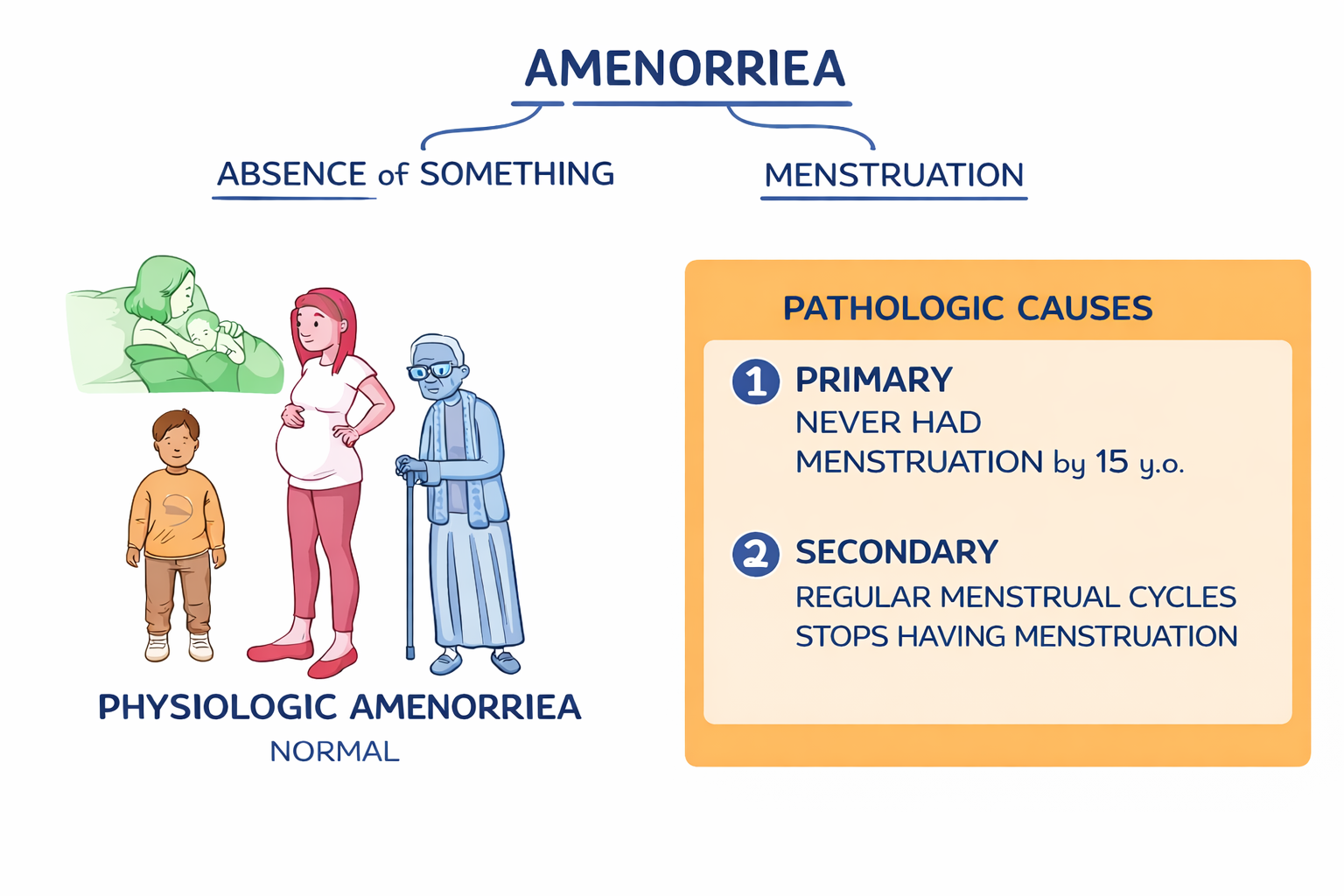

Amenorrhea literally means absence of menstruation. It can be1

Physiologic (normal) — during childhood, pregnancy, lactation, and menopause.

Pathologic — when menstruation fails to begin or unexpectedly stops.

Primary amenorrhea is defined as2

No menarche by age 15 years, despite normal secondary sexual characteristics

No menarche by age 13 years, in the absence of secondary sexual characteristics

No menstruation within 5 years, of thelarche (breast development)

These definitions reflect contemporary consensus guidelines from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and international endocrine societies.

Although relatively uncommon, affecting approximately 0.3–0.5% of adolescents globally, primary amenorrhea represents a diverse spectrum of embryologic, genetic, endocrine, and structural disorders3,4

The Physiology: The Orchestra of the HPO Axis5–7

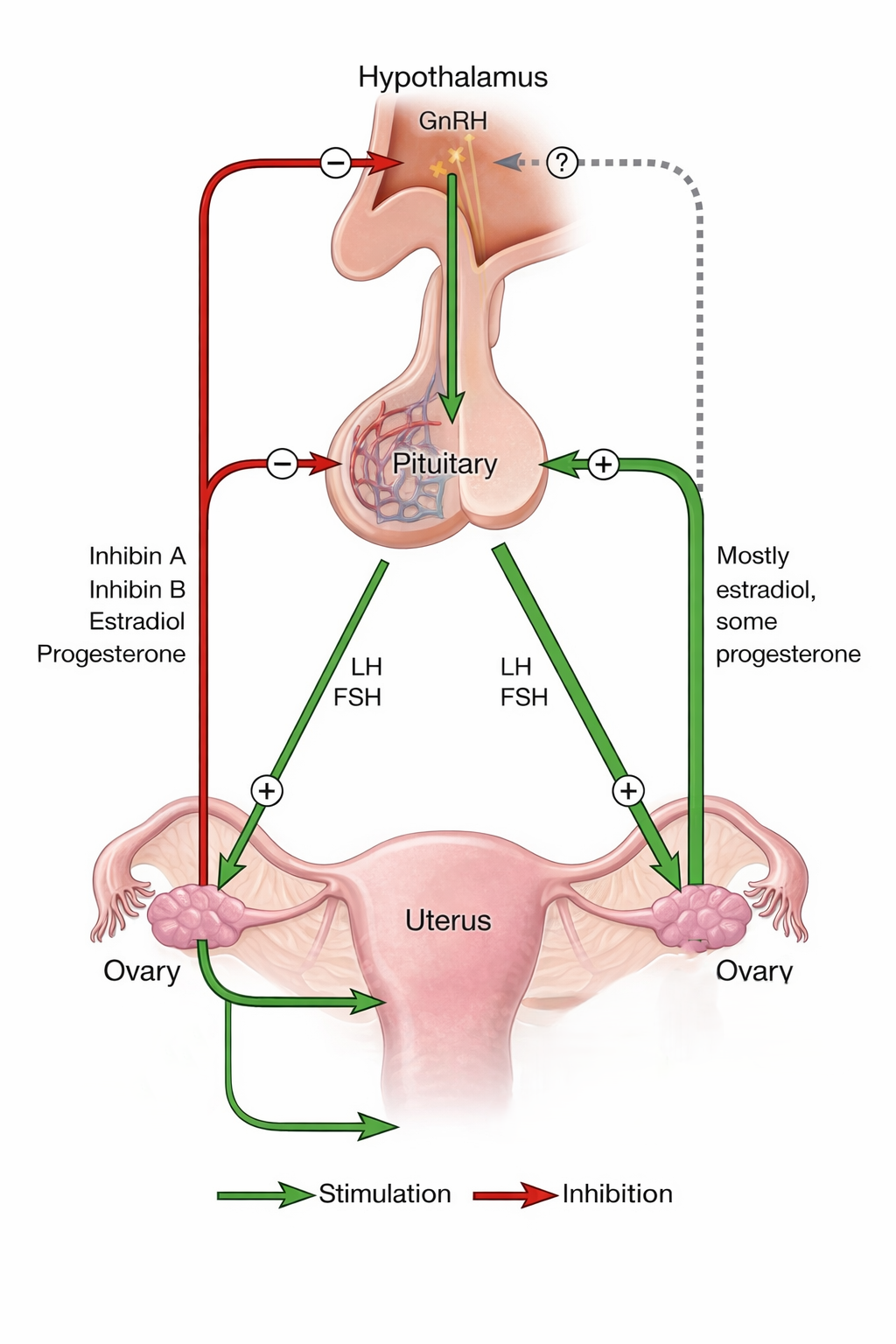

Menstruation is the visible outcome of a precisely regulated neuroendocrine cascade. The hypothalamus releases pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which stimulates the anterior pituitary to secrete follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).

These hormones act on the ovaries, promoting estrogen and progesterone production. In turn, estrogen prepares the endometrium, and progesterone stabilizes it. When progesterone levels fall, the endometrial lining sheds — resulting in menstruation.

Primary amenorrhea arises when this Hypothalamic Pituitary ovarian axis (HPO) fails at any level: hypothalamic signaling, pituitary secretion, ovarian function, uterine development, or outflow tract patency.

The four major structural and genetic causes of primary amenorrea are the following

Müllerian Agenesis (MRKH Syndrome)8–10

Pathophysiology

Müllerian agenesis, also referred to as müllerian aplasia, Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome, or vaginal agenesis, arises from absent or incomplete development of the Müllerian ducts during early embryogenesis, structures that normally give rise to the uterus, cervix, and the upper two-thirds of the vagina. In typical male (46,XY) development, these ducts regress under the influence of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) secreted by Sertoli cells of the fetal testes

Because the ovaries arise from a different embryologic origin, ovarian development and estrogen production remain intact. As a result, patients experience normal puberty and develop secondary sexual characteristics. However, the uterus, cervix, and upper two-thirds of the vagina are absent or severely underdeveloped. Without a uterus, there is no endometrial lining to proliferate or shed, and menstruation cannot occur despite normal hormonal signaling.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is typically established when pelvic imaging reveals an absent or rudimentary uterus in an adolescent with normal breast development and a 46,XX karyotype. Hormonal studies usually demonstrate normal FSH, LH, and estradiol levels, confirming intact ovarian function. MRI may be employed for detailed pelvic anatomy, and renal imaging is often recommended because Müllerian anomalies can coexist with renal malformations.

Treatment

Management focuses on functional and psychosocial outcomes. First-line therapy for vaginal agenesis involves progressive non-surgical dilation techniques to create a functional vaginal canal. Surgical options are reserved for cases where dilation fails. Fertility is not possible without a uterus; however, in vitro fertilization with a gestational carrier provides a reproductive option. Psychological counseling is essential, as the diagnosis can profoundly affect identity and future planning.

Turner Syndrome (45,X)11–13

Pathophysiology

Turner syndrome arises from complete or partial monosomy of one X chromosome, leading to accelerated loss of ovarian follicles during fetal and early postnatal life. The ovaries undergo fibrotic transformation into streak gonads incapable of producing estrogen. Without estrogen, pubertal development is incomplete and the endometrium never undergoes cyclical stimulation. The pituitary responds to ovarian failure by elevating FSH and LH levels, producing a hypergonadotropic hypogonadism pattern.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is confirmed through karyotype analysis demonstrating 45,X or mosaic variants. Laboratory findings show markedly elevated FSH and LH with low estradiol levels. Pelvic ultrasound typically reveals streak ovaries and a small prepubertal uterus. Given the systemic nature of Turner syndrome, cardiac evaluation and renal imaging are recommended to identify associated anomalies.

Treatment

Management involves growth hormone therapy during childhood to optimize adult height, followed by carefully titrated estrogen replacement therapy to induce puberty and support bone health. Progesterone is later introduced to protect the endometrium once adequate estrogenization is achieved. Fertility options include assisted reproductive technologies using donor oocytes, although cardiovascular risk assessment is critical before pregnancy is considered.

Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (AIS)14–16

Pathophysiology

In complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, individuals possess a 46,XY karyotype and functioning testes that produce testosterone and anti-Müllerian hormone. Anti-Müllerian hormone causes regression of Müllerian ducts, preventing uterine formation. However, mutations in the androgen receptor prevent tissues from responding to testosterone. Because testosterone cannot exert its masculinizing effects, external genitalia develop along female lines. Aromatization of testosterone to estrogen drives breast development, but the absence of a uterus precludes menstruation.

Diagnosis

Evaluation reveals a 46,XY karyotype, elevated testosterone levels within the male range, and absent uterus on imaging. Testes are often located intra-abdominally or within the inguinal canal. Pubic and axillary hair may be sparse due to androgen resistance.

Treatment

Management includes gonadectomy after puberty to reduce malignancy risk, followed by estrogen replacement therapy. Comprehensive counseling addressing gender identity, fertility implications, and psychosocial well-being is central to care.

Imperforate Hymen17–20

Pathophysiology

Imperforate hymen represents a failure of the hymenal membrane to perforate during development. In this condition, the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis functions normally, and the uterus builds and sheds endometrial tissue in response to hormonal cycling. However, the absence of a vaginal opening prevents menstrual blood from exiting, leading to accumulation within the vagina and uterus. The result is cyclic pelvic pain and progressive distension.

Diagnosis

Physical examination typically reveals a tense, bulging hymenal membrane without an opening. Ultrasound may demonstrate hematocolpos or hematometra. Hormonal studies are usually normal.

Treatment

A simple surgical procedure, hymenectomy, creates an opening that allows normal menstrual flow. Prognosis is excellent, with immediate symptom resolution following correction.

Modern Diagnostic Approach21–24

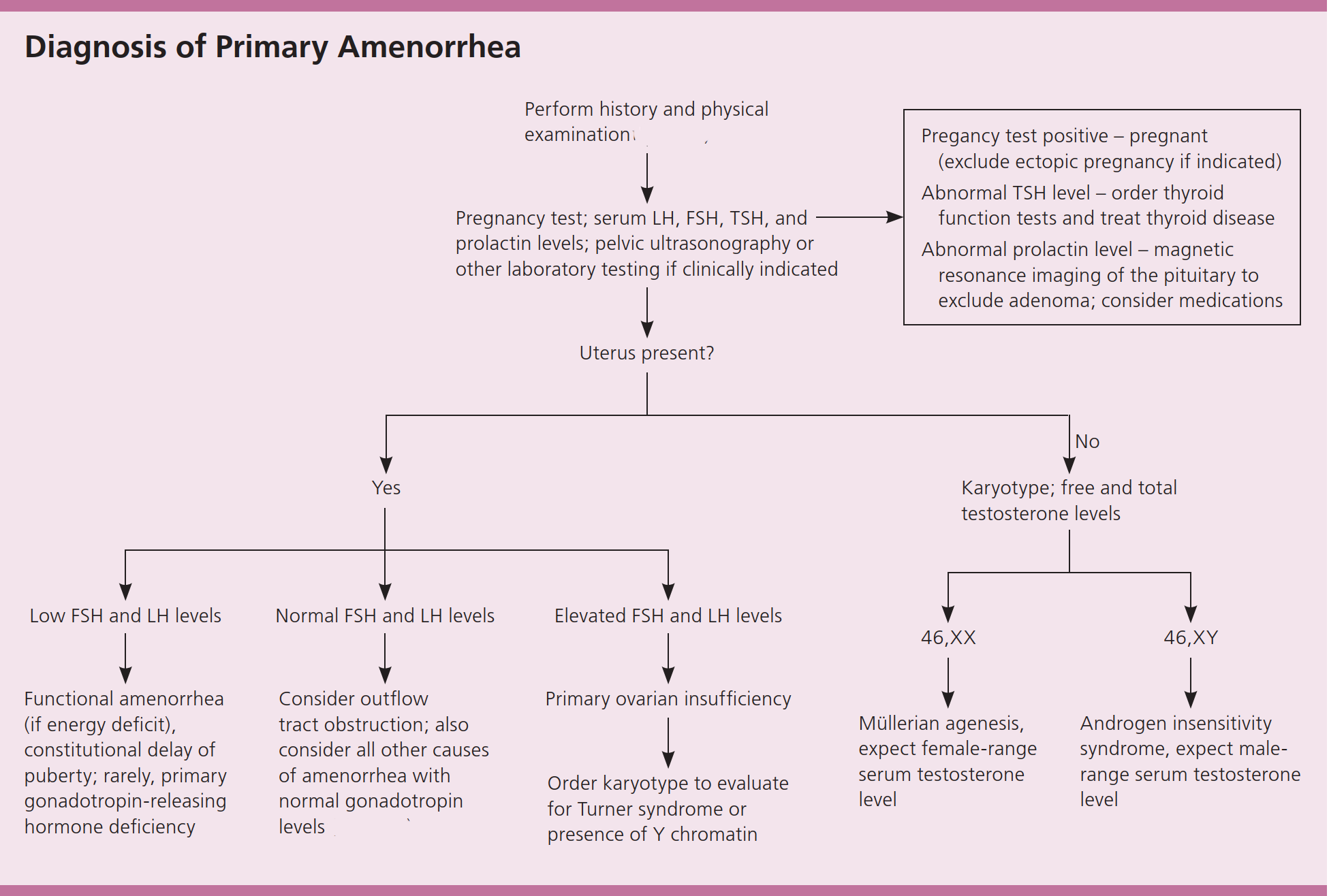

Evaluation of primary amenorrhea begins with a simple but essential principle: always exclude pregnancy, regardless of age or reported history. From there, the clinician turns to a careful assessment of pubertal development, noting breast maturation, growth pattern, and the presence or absence of pubic and axillary hair. These physical findings often provide the first clues about whether estrogen exposure has occurred and whether the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis has been activated.

A diagnostic approach to primary amenorrhea25

Once pregnancy has been excluded and pubertal development assessed, targeted biochemical testing provides the next layer of insight. Measurement of follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and estradiol allows differentiation between central hypogonadism and primary ovarian insufficiency. Markedly elevated gonadotropins with low estradiol indicate ovarian failure and loss of follicular function. In contrast, normal gonadotropins and estradiol in the setting of an absent uterus on imaging suggest a structural or receptor-level condition such as Müllerian agenesis or complete androgen insensitivity. When pelvic anatomy is intact but the patient presents with cyclic pain and no visible outflow, an obstructive anomaly of the genital tract must be considered.

Pelvic ultrasound serves as the first-line imaging modality to evaluate uterine presence, ovarian morphology, and potential hematocolpos, while magnetic resonance imaging may provide greater anatomical detail when needed. Increasingly, modern evaluation extends beyond anatomy and hormone levels. Advances in next-generation sequencing now enable identification of rare monogenic causes of gonadal dysgenesis and disorders of sex development, offering molecular confirmation where clinical findings alone are insufficient. In this way, the contemporary diagnostic approach integrates clinical observation, endocrine physiology, imaging precision, and genomic insight to move from symptom to mechanism with clarity and care.

Conclusion

Primary amenorrhea is not simply the absence of menstrual bleeding; it is a signal that a developmental process has diverged from its expected path. It may arise from embryologic failure of Müllerian structures, chromosomal abnormalities that impair ovarian development, receptor-level defects that disrupt hormonal signaling, or mechanical obstruction of menstrual flow. Each pathway reflects a different layer of human biology — anatomy, genetics, endocrinology, or receptor physiology — yet all converge on the same clinical presentation. Modern medicine approaches primary amenorrhea with structured diagnostic reasoning, molecular precision, and multidisciplinary care that integrates endocrinology, gynecology, genetics, and psychological support. When evaluated thoughtfully, this condition becomes not merely a disorder of menstruation but a window into the intricacy of human development and the responsibility of compassionate clinical practice.