Introduction1,2

Schizophrenia is one of the most enigmatic and devastating psychiatric illnesses, affecting nearly 24 million people worldwide. First formally described in the late 19th century by Emil Kraepelin as dementia praecox—a premature mental decline—it was later reframed by Eugen Bleuler, who coined the term schizophrenia (“split mind”) to reflect the fragmentation of thought, perception, and emotion.

The condition is not, as often misconstrued, a “split personality.” Instead, it is a disorder of integration, where brain networks fail to synchronize reality, leading to hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thought, and emotional flattening. Let me explain this complexity

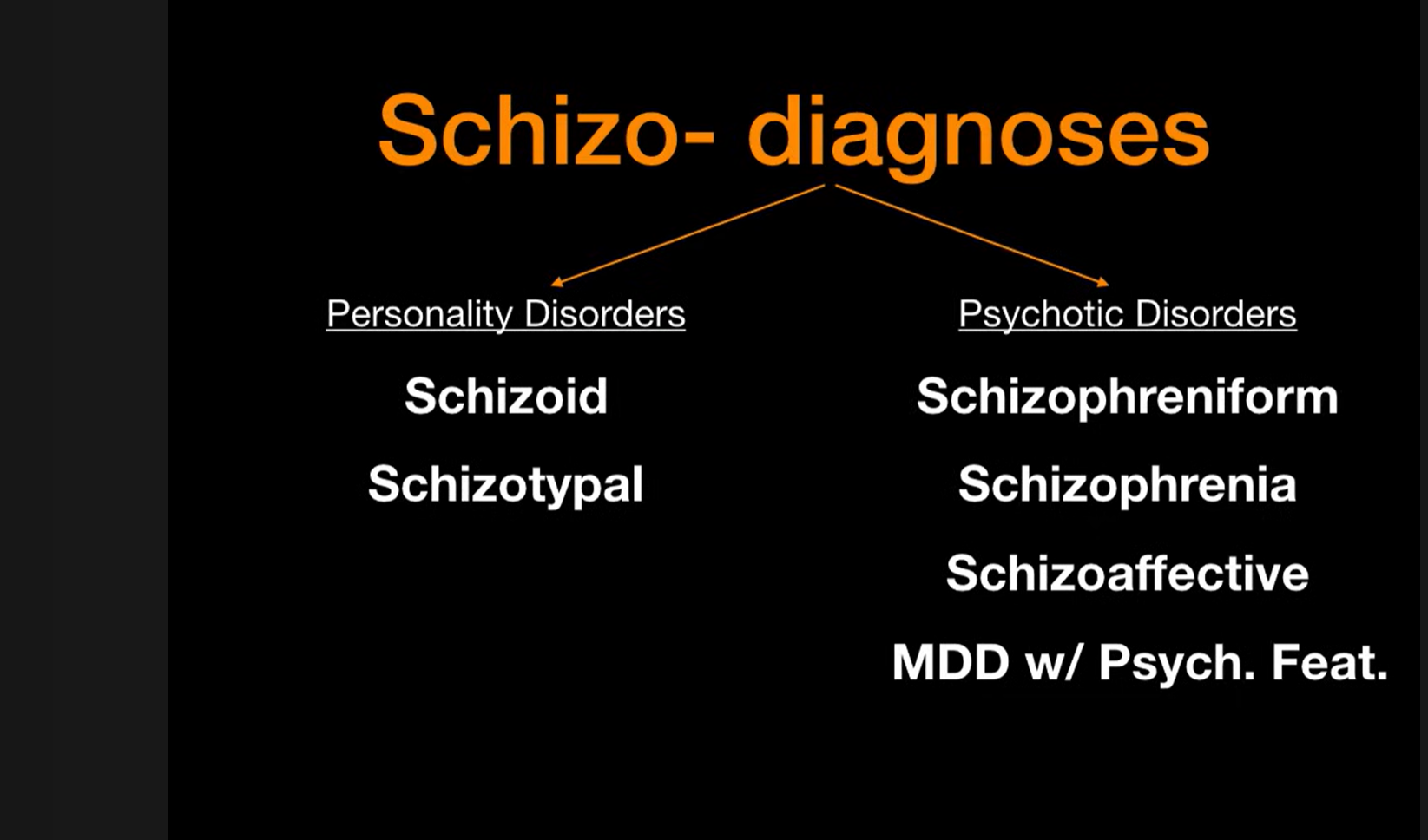

The illustartion above categorizes “schizo-” related conditions into two groups:

Personality Disorders (schizoid, schizotypal) (…additional context is provided in the sidebar.”)

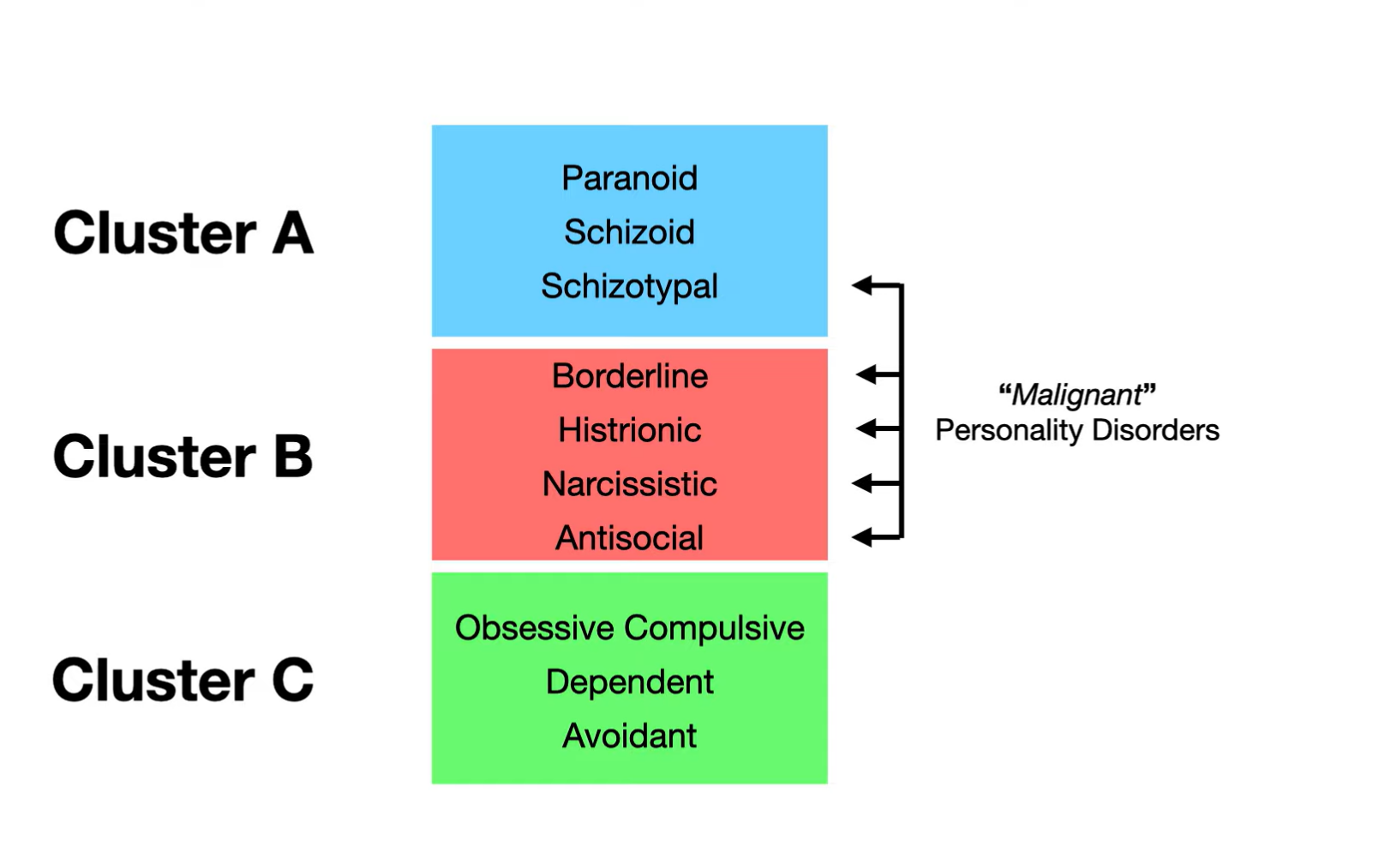

Personality disorders are enduring patterns of maladaptive behaviors, cognitions, and emotions that impair functioning. They are common in high-risk groups (e.g., incarceration, young males, low education). In those diagnosed before age 18, symptoms must persist for >1 year to establish a diagnosis. They are divide into following clusters.

Cluster A:

Paranoid Personality Disorder:

- Distrustful, suspicious, and accusatory;

- Interpret others’ motives as malevolent.

- Reality testing remains intact (vs. psychotic disorders)

Schizoid Personality Disorder:

- Socially detached, reclusive with blunted affect and indifference to praise or criticism.

- Prefer solitary activities.

- No motivation for relationship (Vs Avoidant)

Schizotypal Personality Disorder:

- Eccentric behavior, odd beliefs or magical thinking, and interpersonal deficits.

- Considered a bridge between personality and psychotic disorders.

Cluster B:

Borderline Personality Disorder:

- Marked by unstable mood, self-image, and relationships.

- High risk of self-harm,

- use of “splitting” (seeing others as all good or all bad), and chronic interpersonal difficulties.

Histrionic Personality Disorder:

- Excessively emotional and attention-seeking

- often overly concerned with appearance and sexualized behavior.

- Crave being the center of attention.

Narcissistic Personality Disorder:

- Grandiose, entitled, lacking empathy.

- Exaggerate accomplishments and may respond with rage when criticized.

Antisocial Personality Disorder:

- Disregard for others’ rights, manipulative, criminal or violent behavior. - Often linked to childhood conduct disorder

- superficially charming but without remorse.

Cluster C:

Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD):

- Preoccupied with order, control, and perfectionism.

- Behavior is ego-syntonic (consistent with self-image), unlike OCD.

Avoidant Personality Disorder:

- Hypersensitive to rejection, low self-esteem, desire relationships but avoid them due to intense social anxiety.

Dependent Personality Disorder:

- Rely on others for support and validation

- struggle with decision-making

- may tolerate abusive or controlling relationships.

Psychotic Disorders (schizophreniform, schizophrenia, schizoaffective, and major depressive disorder with psychotic features).

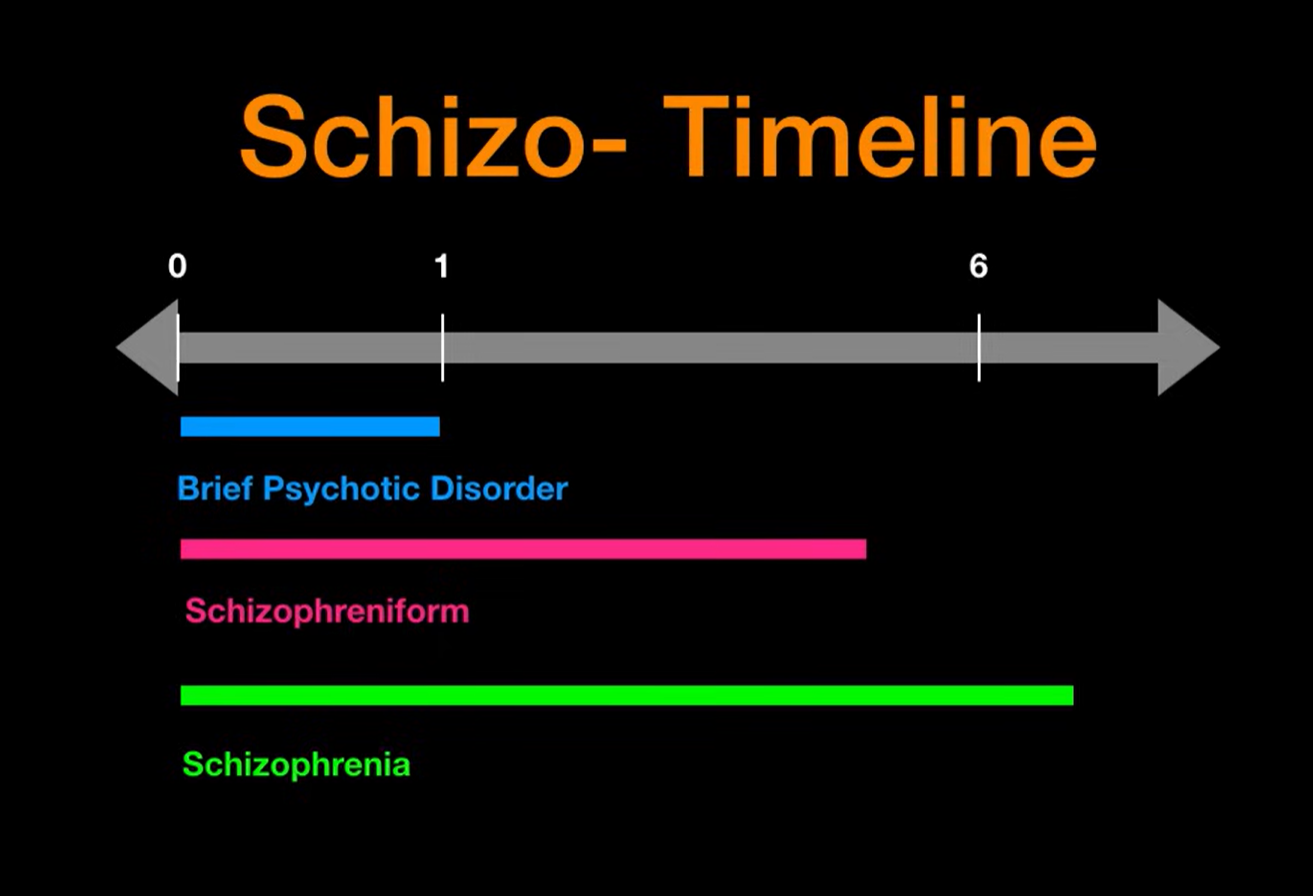

It highlights how similar terminology can represent distinct diagnostic categories within psychiatry. Schizoprenia comes under the psychotic disorder with following timeline.

This timeline illustrates the duration criteria for schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Brief Psychotic Disorder lasts less than 1 month, Schizophreniform Disorder persists between 1 and 6 months, while Schizophrenia is diagnosed when symptoms extend beyond 6 months. These temporal distinctions help guide accurate diagnosis.

Pathophysiology5–8

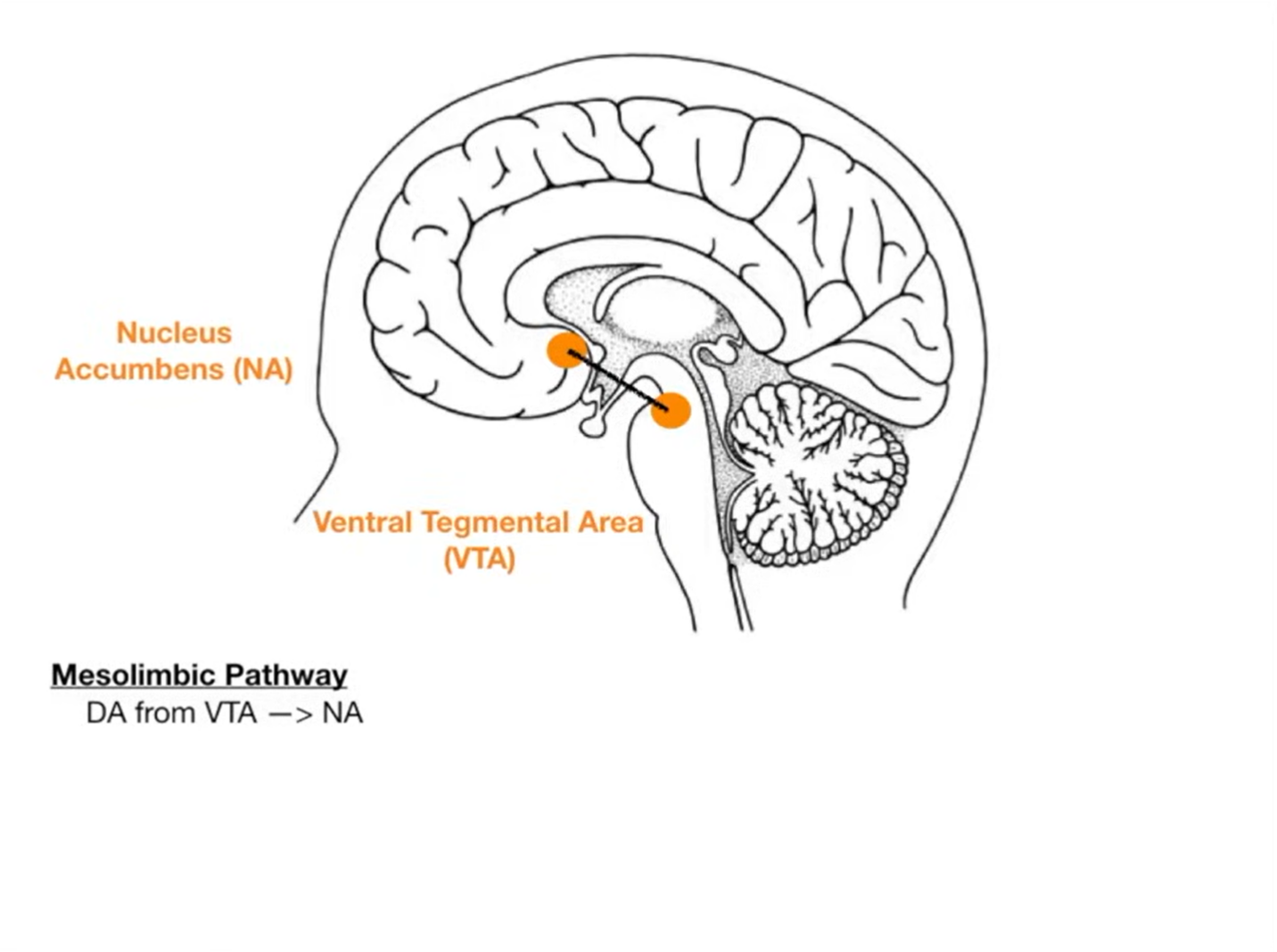

In healthy brains, a delicate interplay of neurotransmitters—dopamine, glutamate, and acetylcholine—allows for coherent thought and adaptive behavior. In schizophrenia, this balance is disrupted:

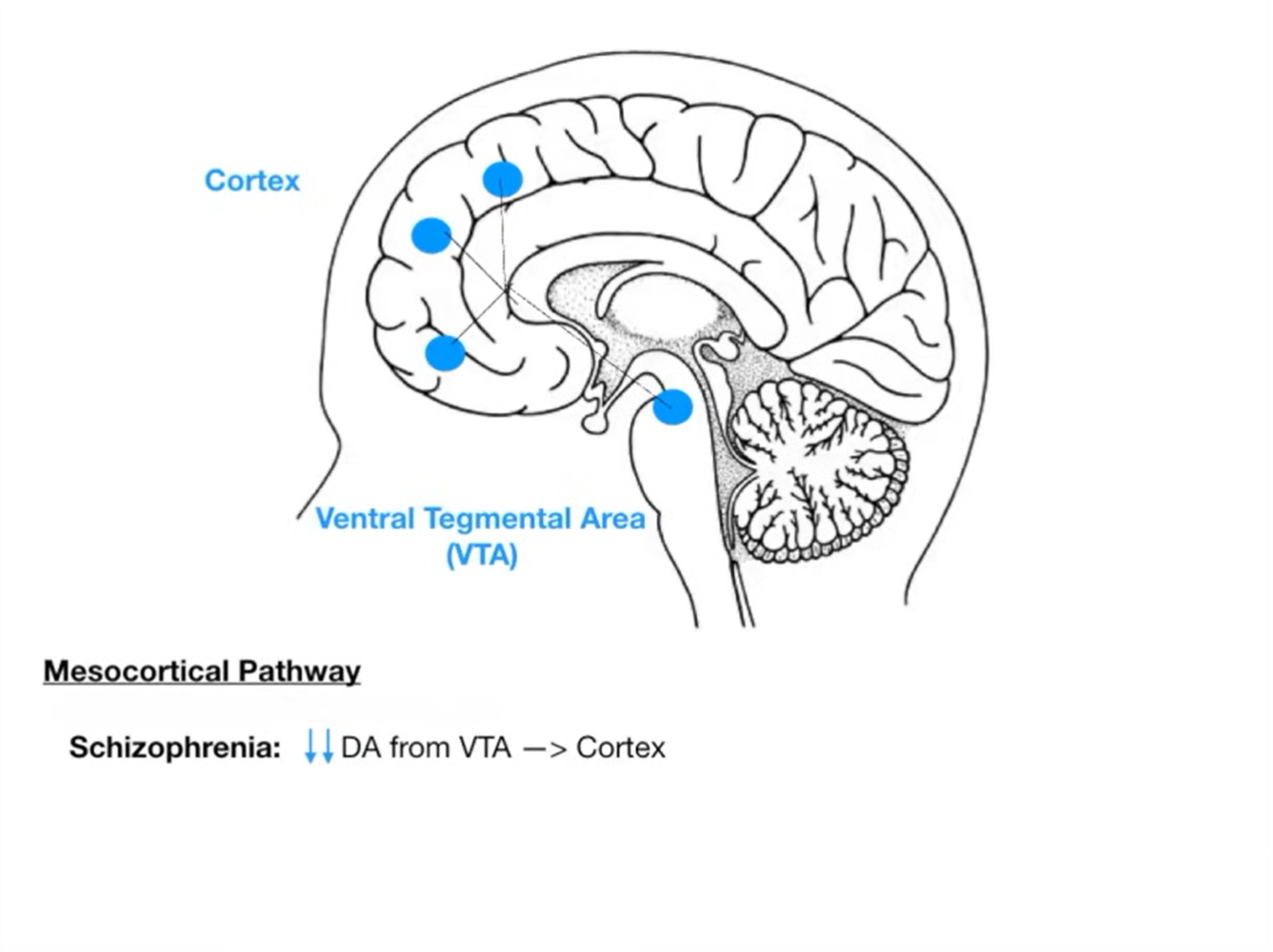

Dopamine hyperactivity in mesolimbic pathways is linked to positive symptoms (hallucinations, delusions).

Dopamine hypoactivity in mesocortical pathway contributes to negative symptoms (apathy, social withdrawal).

Glutamatergic dysfunction and microglial overactivation are increasingly recognized as contributors to cognitive impairment and neuroinflammation.

Traditionally, schizophrenia was divided into paranoid, catatonic, hebephrenic, and undifferentiated subtypes. Modern classification (DSM-5) instead emphasizes a dimensional approach, grading symptom domains: positive, negative, cognitive, and affective

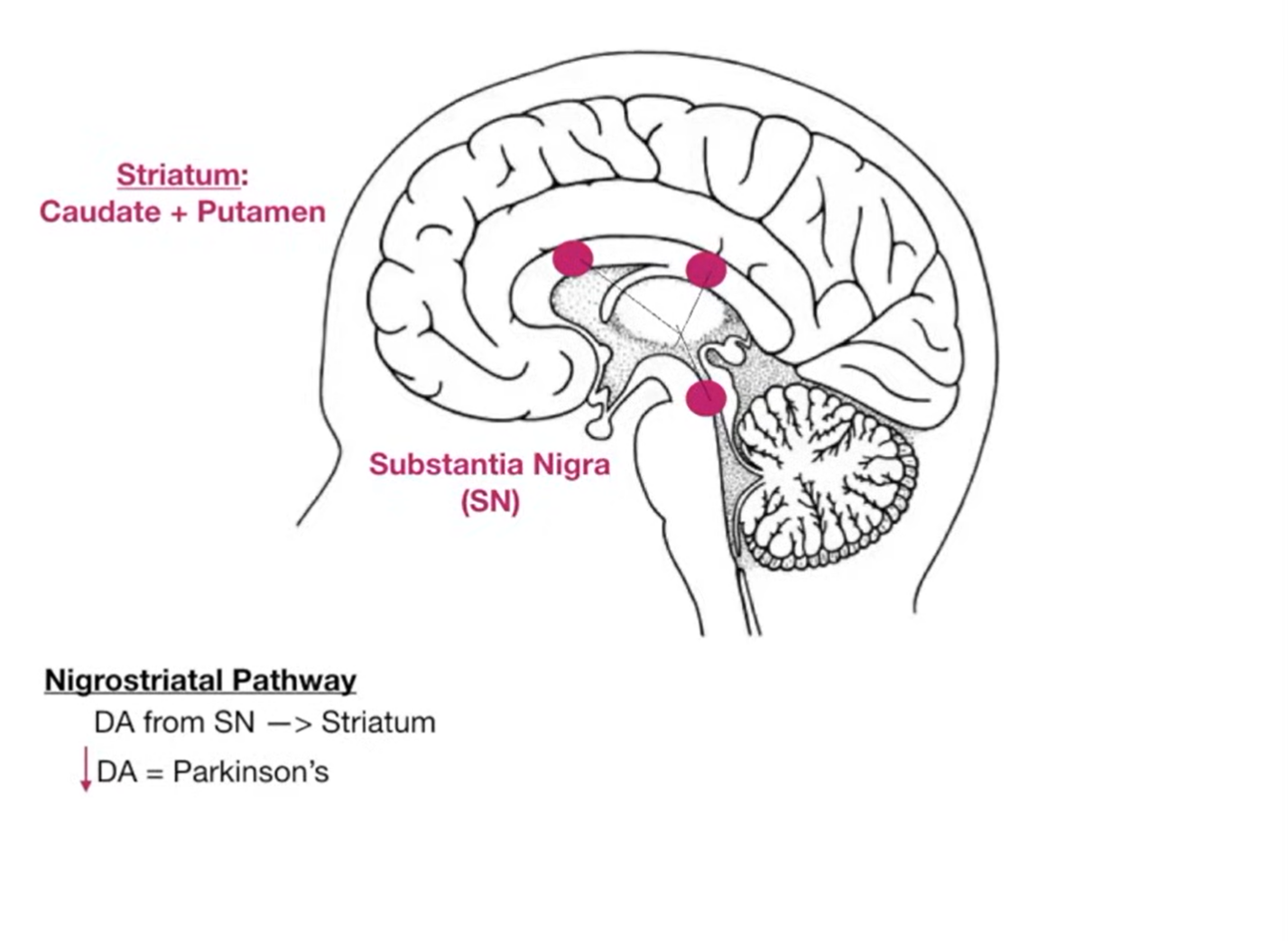

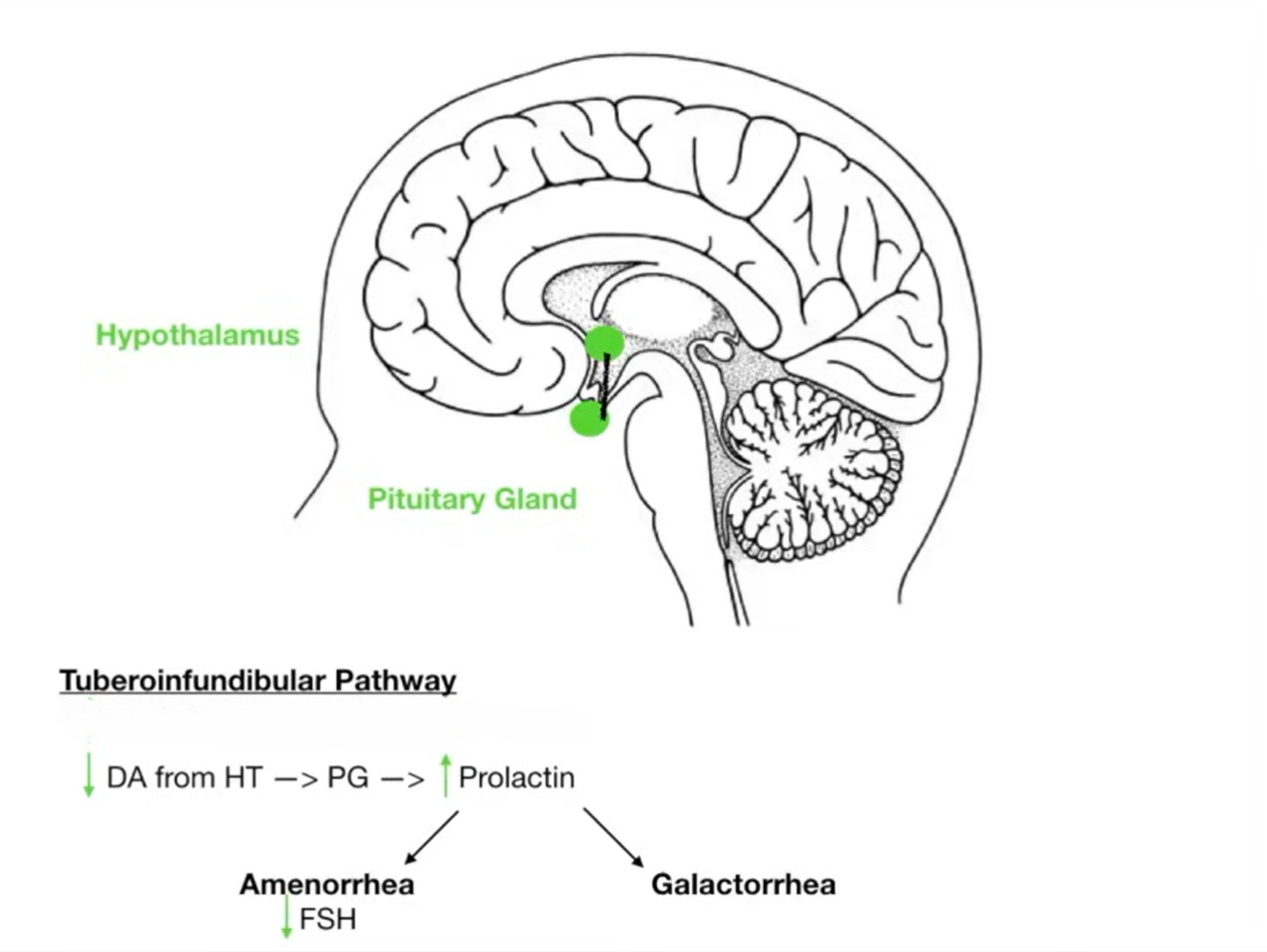

Important Dopaminergic Pathways altered with the use of antipsychotics are See Nigrostriatal Pathway and Tuberoinfundibular Pathway.

Causes9,10

No single cause exists. Instead, schizophrenia arises from an interplay of:

Genetic vulnerability: over 100 loci identified, including COMT, DISC1,and NRG1.

Neurodevelopmental insults: in utero infections, hypoxia, obstetric complications.

Environmental triggers: cannabis use, urban upbringing, trauma.

Neurobiological changes: synaptic pruning abnormalities, impaired myelination, and altered cortical connectivity

Cellular Mechanism11–13

At the cellular level, schizophrenia is marked by:

Aberrant synaptic pruning during adolescence, potentially linked to complement system overactivity.

Hypofunction of NMDA receptors on cortical interneurons, disrupting excitatory–inhibitory balance.

Dopaminergic dysregulation, where striatal dopamine synthesis is elevated, but prefrontal dopamine tone is deficient.

Cholinergic signaling defects, especially involving M₁ and M₄ muscarinic receptors, which modulate dopamine and glutamate release.

a neurochemical storm, impairing perception, memory, and executive function

These converging pathways create a neurochemical storm, impairing perception, memory, and executive function.

Current Research Progress14–16

For decades, antipsychotic drug development was stagnant—anchored on dopamine D₂ receptor antagonism. In September 2024, however, the U.S. FDA approved Cobenfy developed by Bristol Myers Squibb, the first truly novel therapy in decades.

Cobenfy is a fixed-dose oral capsule combining:

Xanomeline: a selective muscarinic M₁/M₄ agonist that restores cortical–striatal signaling without blocking dopamine receptors.

Trospium chloride:, a peripheral muscarinic antagonist that prevents unwanted cholinergic side effects, such as gastrointestinal upset.

Why It Matters

Unlike traditional antipsychotics, Cobenfy avoids dopamine blockade, which means a lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms (movement disorders). Clinical trials showed significant improvements in both positive and negative symptoms, measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

Limitations

A recent Phase 3 trial (ARISE) testing Cobenfy as an add-on therapy showed only modest benefit over placebo. While its role as monotherapy is established, its utility as an adjunct remains under scrutiny.

Current Treatment17

The management of schizophrenia has historically relied on antipsychotic medications, which remain the cornerstone of therapy. Over the years, these agents have evolved in both mechanism and tolerability, though no treatment is universally effective. Clinical response is highly variable, requiring careful titration and monitoring.

Antipsychotic Drugs

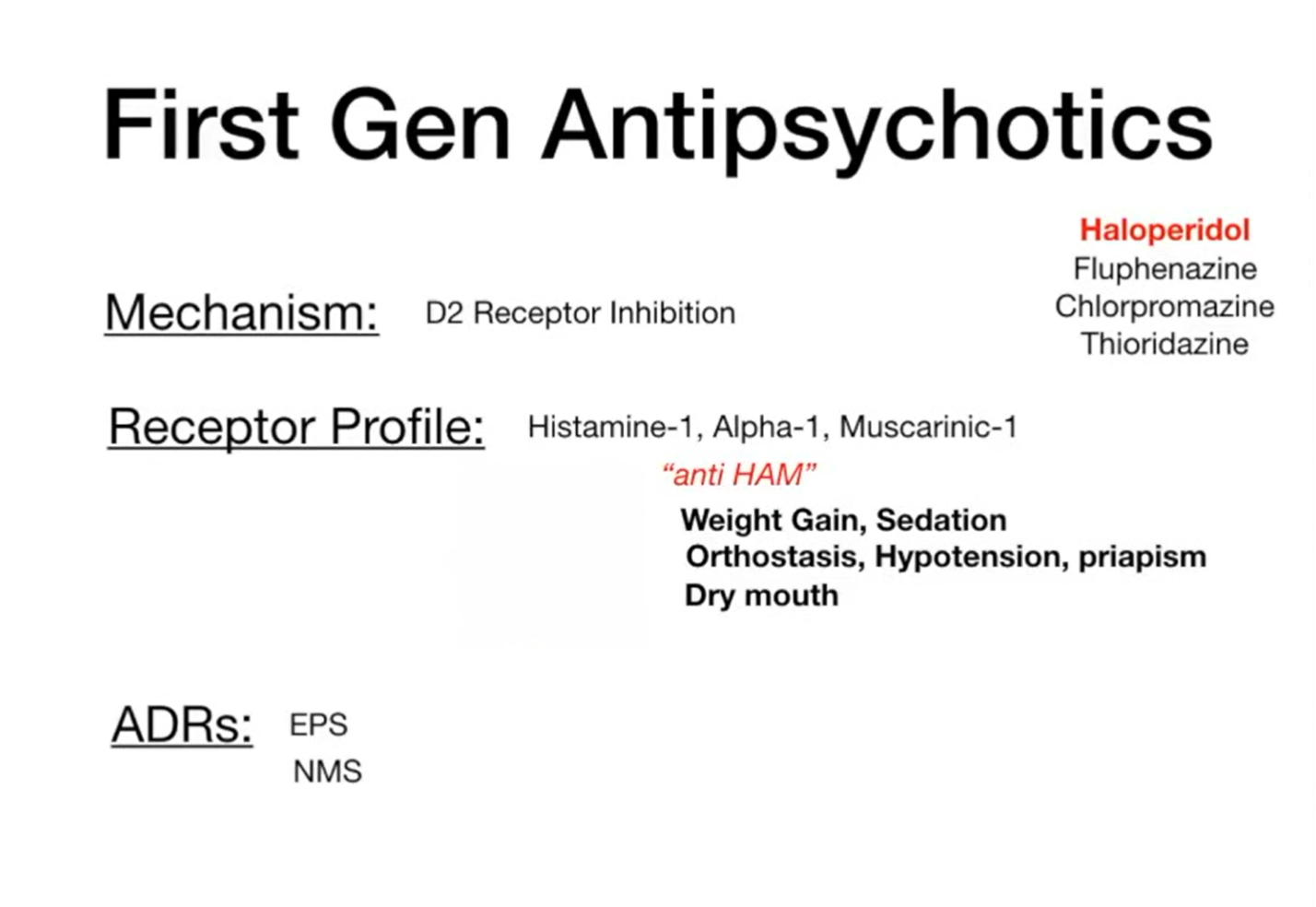

First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs):

Also called “typical” antipsychotics, these drugs act predominantly by blocking dopamine D₂ receptors in the brain. While effective for reducing positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions, they are often associated with acute extrapyramidal side effects (dystonia, parkinsonism, akathisia) and hyperprolactinaemia.

The five major classes are:

Phenothiazines: chlorpromazine, fluphenazine decanoate,levomepromazine, pericyazine, prochlorperazine, promazine, trifluoperazine

Butyrophenones: haloperidol, benperidol

Thioxanthenes: flupentixol, zuclopenthixol

Diphenylbutylpiperidines: pimozide

Substituted benzamides: sulpiride

The illustration below depicts the receptor binding profile of first-generation antipsychotics. In addition to dopamine D₂ receptor blockade, these agents exhibit anti-HAM activity—antagonism at histamine H₁, α₁-adrenergic, and muscarinic M₁ receptors. These off-target effects underlie common adverse outcomes, including weight gain and sedation (H₁ blockade), orthostatic hypotension and priapism (α₁ blockade), and dry mouth (M₁ blockade).

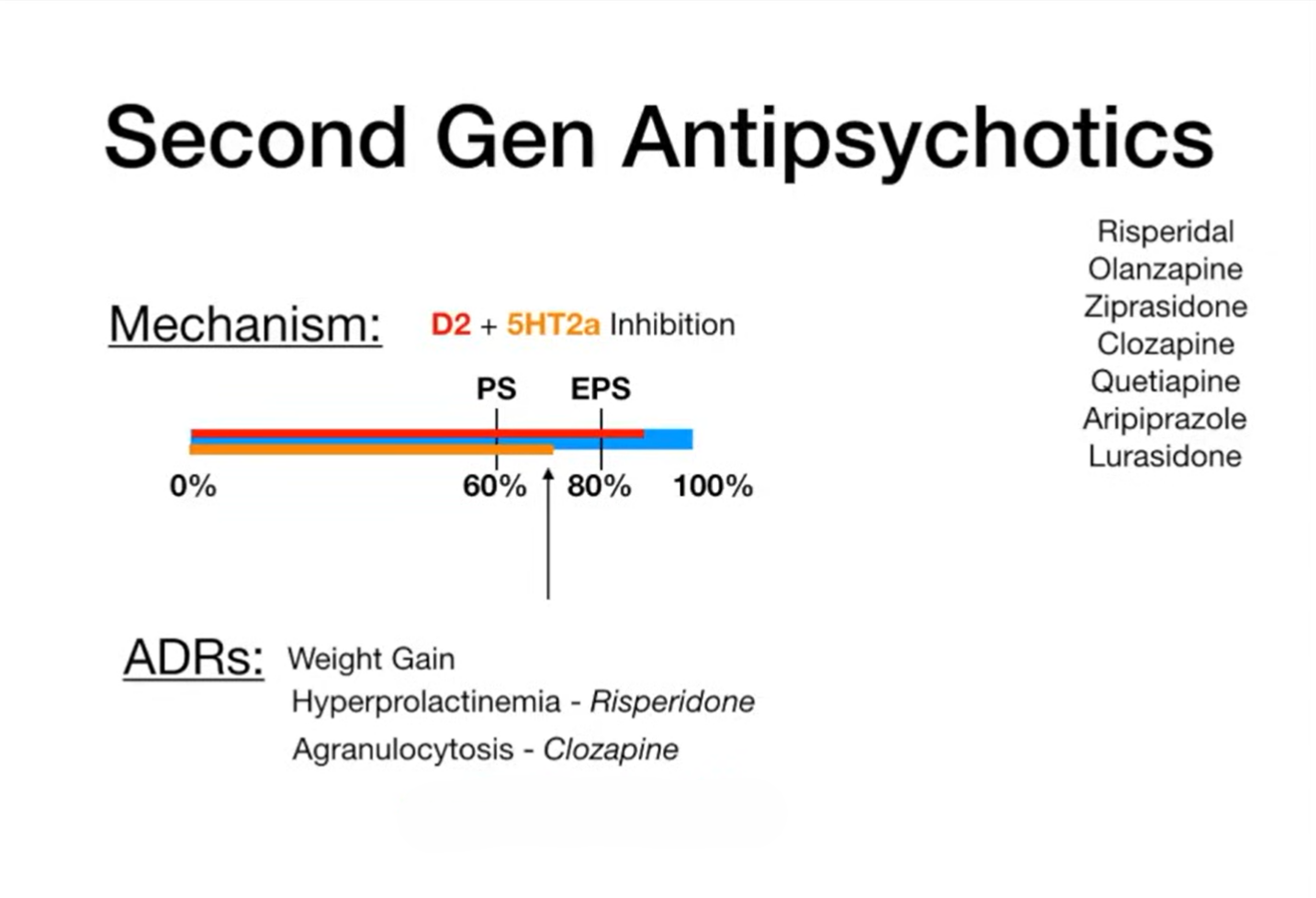

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs):

These “atypical” drugs act on a broader range of receptors, including serotonin 5-HT₂A, in addition to dopamine D₂. They are generally less likely to cause movement disorders and tardive dyskinesia, but they carry significant risks of metabolic complications such as weight gain, dyslipidemia, and glucose intolerance.

The blue bar (0–100%) in the illustration below, depicts dopamine D₂ receptor occupancy. Clinical benefit, particularly improvement of positive symptoms (PS), emerges once occupancy reaches approximately 60%. However, when blockade exceeds 80%, the likelihood of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS)—including rigidity, tremor, and dystonia—markedly increases, a pattern most evident with first-generation antipsychotics. In contrast, second-generation agents combine D₂ antagonism with 5-HT₂A receptor inhibition, which modulates dopamine release in the nigrostriatal pathway. This dual mechanism maintains receptor occupancy within the therapeutic “sweet spot” of 60–80%, effectively treating positive symptoms while minimizing the risk of EPS.

Common examples include: Amisulpride, Aripiprazole, Asenapine, Cariprazine, Clozapine, Lurasidone, Olanzapine, Paliperidone, Quetiapine, Risperidone

Depot injections (Long-acting injectables, LAIs):

For patients struggling with adherence, long-acting injectable formulations offer an effective solution. First-generation depot injections are associated with higher rates of extrapyramidal side effects, while second-generation depots (aripiprazole, paliperidone, risperidone, olanzapine embonate) offer a better tolerability profile. Zuclopenthixol decanoate has been noted as potentially more effective in relapse prevention than some other first-generation depots.

Ultimately, the choice of antipsychotic—oral or depot—depends on individual response, side effect profile, and patient preference, with dosage and intervals titrated for optimal effect.

Clozapine: The Special Case18,19

While most antipsychotics have comparable efficacy, clozapine is the clear exception.

It is the only antipsychotic proven effective in treatment-resistant schizophrenia (after failure of ≥2 other antipsychotics).

It also shows a unique benefit in reducing suicidality in patients with schizophrenia.

Because of the risk of agranulocytosis, myocarditis, and seizures, its use requires strict blood monitoring and careful patient selection.

➡️ Thus, clozapine is reserved for difficult-to-treat cases but remains the gold standard when other therapies fail.

Side-effects of antipsychotic drugs

Overview

There is little difference in efficacy between most antipsychotic drugs (other than clozapine), and response/tolerability varies widely. No single first-line antipsychotic suits all patients; properties of individual agents should be considered and discussed with patients/carers. Both first- and second-generation antipsychotics have common side-effects that significantly contribute to non-adherence and discontinuation.

Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) movement

EPS are dose-related and most likely with high doses of high-potency first-generation agents (piperazine phenothiazines such as fluphenazine decanoate and trifluoperazine; butyrophenones such as benperidol and haloperidol) and with first-generation depot preparations. They are less common with some second-generation antipsychotics—particularly clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and aripiprazole—but depend on dose, class, and individual susceptibility.

- Parkinsonian symptoms (bradykinesia, tremor) – more common in elderly females or those with pre-existing neurological damage; gradual onset.

- Dystonia (acute muscle spasm) – more common in young males; can appear within hours of initiation.

- Akathisia (restlessness) – occurs within hours to weeks of starting or increasing dose; can mimic psychotic agitation.

- Tardive dyskinesia (involuntary oro-facial/limb movements) – with long-term or high-dose therapy or after discontinuation; may be irreversible.

If parkinsonian symptoms occur, review treatment to reduce exposure to high-dose/high-potency drugs. Antimuscarinics can relieve symptoms but should not be used routinely for prophylaxis.

Tardive dyskinesia is the most serious late EPS (more common in elderly females) without a fully satisfactory treatment. Review therapy regularly; make dose/drug changes gradually over weeks–months. Some manufacturers advise withdrawing the drug at earliest signs (e.g., fine vermicular tongue movements) to prevent progression.

Hyperprolactinaemia endocrine

Most antipsychotics increase prolactin (dopamine normally inhibits prolactin release). Aripiprazole lowers prolactin dose-dependently (partial D₂ agonist). Risperidone, amisulpride, sulpiride and many first-generation drugs most often cause symptomatic hyperprolactinaemia, which is very rare with aripiprazole, asenapine, cariprazine, clozapine, and quetiapine.

Symptoms: sexual dysfunction, low bone mineral density, menstrual disturbance, breast enlargement, galactorrhoea, and a possible ↑ risk of breast cancer.

Sexual dysfunction sexual health

Reported with all antipsychotics; physical/psychiatric illness and substance misuse may contribute. Mechanisms include reduced dopamine transmission and hyperprolactinaemia (↓ libido), antimuscarinic effects (arousal disorders), and α1-blockade (erection/ejaculation issues).

Higher prevalence with risperidone, haloperidol, olanzapine; lowest risk with aripiprazole and quetiapine. Consider dose reduction, discontinuation (when appropriate), or switching if antipsychotic-induced.

Cardiovascular side-effects & QT prolongation cardiac

Tachycardia, arrhythmias, and hypotension can occur. QT-interval prolongation is a key concern (notably with pimozide). Risk increases with IV antipsychotics or exceeding recommended maximum daily doses or combining QT-prolonging agents.

Lower QT-liability agents: aripiprazole, asenapine, clozapine, flupentixol, fluphenazine decanoate, loxapine, olanzapine, paliperidone, prochlorperazine, risperidone, sulpiride.

Hypotension (postural) blood pressure

Common during initial titration; may persist. Can cause syncope and falls, especially in older adults. Among SGAs, clozapine and quetiapine most likely to cause postural hypotension. Slow titration helps mitigate risk.

Hyperglycaemia & diabetes metabolic

Schizophrenia is associated with insulin resistance/diabetes; antipsychotics further increase risk. Some evidence suggests FGAs may be less diabetogenic than SGAs. Among FGAs, fluphenazine decanoate and haloperidol have lower risk; among SGAs, amisulpride and aripiprazole have the lowest risk.

Weight gain metabolic

All antipsychotics may cause weight gain, with variable risk. Clozapine and olanzapine commonly cause significant gain. Lower-risk agents include amisulpride, asenapine, aripiprazole, cariprazine, haloperidol, lurasidone, sulpiride, trifluoperazine.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) emergency

Rare but potentially fatal: hyperthermia, fluctuating consciousness, rigidity, autonomic dysfunction (fever, tachycardia, labile BP, sweating).

Action: stop the antipsychotic for at least 5 days (often longer) and allow full resolution of signs/symptoms. Bromocriptine and dantrolene have been used in treatment.

Novel Muscarinic Therapy

(Click the title to celebrate 🎉)

In addition to the above antipsychotics, a new anticholinergic/cholinergic agent as discussed above, Cobenfy (xanomeline + trospium) has recently been added to the treatment armamentarium.20,21 Unlike dopamine-blocking agents, Cobenfy targets muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (M₁/M₄),representing the first novel mechanism approved in decades.

Dose: 50/20 to 125/30 mg capsule, taken twice daily on an empty stomach

Adverse effects: Nausea, constipation, hypertension, tachycardia

Counselling: Avoid use in glaucoma, severe hepatic impairment, or urinary retention; educate patients about potential gastrointestinal and cardiovascular side effects

This therapy offers hope for patients who do not respond adequately to dopamine-targeted medications, although long-term real-world data are still being gathered

Conclusion

Schizophrenia is not just a psychiatric disorder—it is a story of disrupted brain circuitry, human suffering, and resilience. While dopamine-targeted drugs transformed care in the mid-20th century, their limitations have long been felt. With the arrival of Cobenfy, science has reopened the door to alternative pathways, particularly cholinergic modulation. Yet, schizophrenia treatment remains a marathon, not a sprint. Success will come from integrating pharmacology, psychotherapy, and social support to empower patients toward recovery and dignity.