HIV in 2025: At a Glance Summary

Epidemiology Current burden

- 39.9M people living with HIV

- 1.3M new infections (2023)

- 630k AIDS-related deaths (2023)

- Progress, but not on track for 2030 goals

Treatment What works now

- Immediate, universal, lifelong ART

- Integrase-based once-daily regimens

- Long-acting injectables: CAB+RIL (q1–2 months)

- Horizon: implants, ≥6-mo injectables, bNAbs

Prevention Scaling protection

- PrEP uptake below 2025 targets

- Options: daily oral, 2-1-1, q2-month CAB

- Lenacapavir depot ~6 months; strong trial data

- Choice models ↑ coverage (e.g., SEARCH)

Cure Where we’re headed

- 7 documented cures via stem-cell transplant

- Functional remission in select controllers

- Combos: reservoir targeting + immunotherapy + gene/cell therapy

- Toward scalable “one-shot” gene-editing strategies

Current HIV Epidemiology1

As we enter 2025, the global HIV epidemic remains both a story of remarkable progress and of unfinished business. According to the UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2024, an estimated 39.9 million people are currently living with HIV worldwide. While advances in treatment have transformed HIV into a manageable chronic condition for many, the epidemic continues to exert a heavy toll. In 2023, 1.3 million new HIV infections were reported, alongside 630,000 AIDS-related deaths, underscoring the continued urgency of the response.

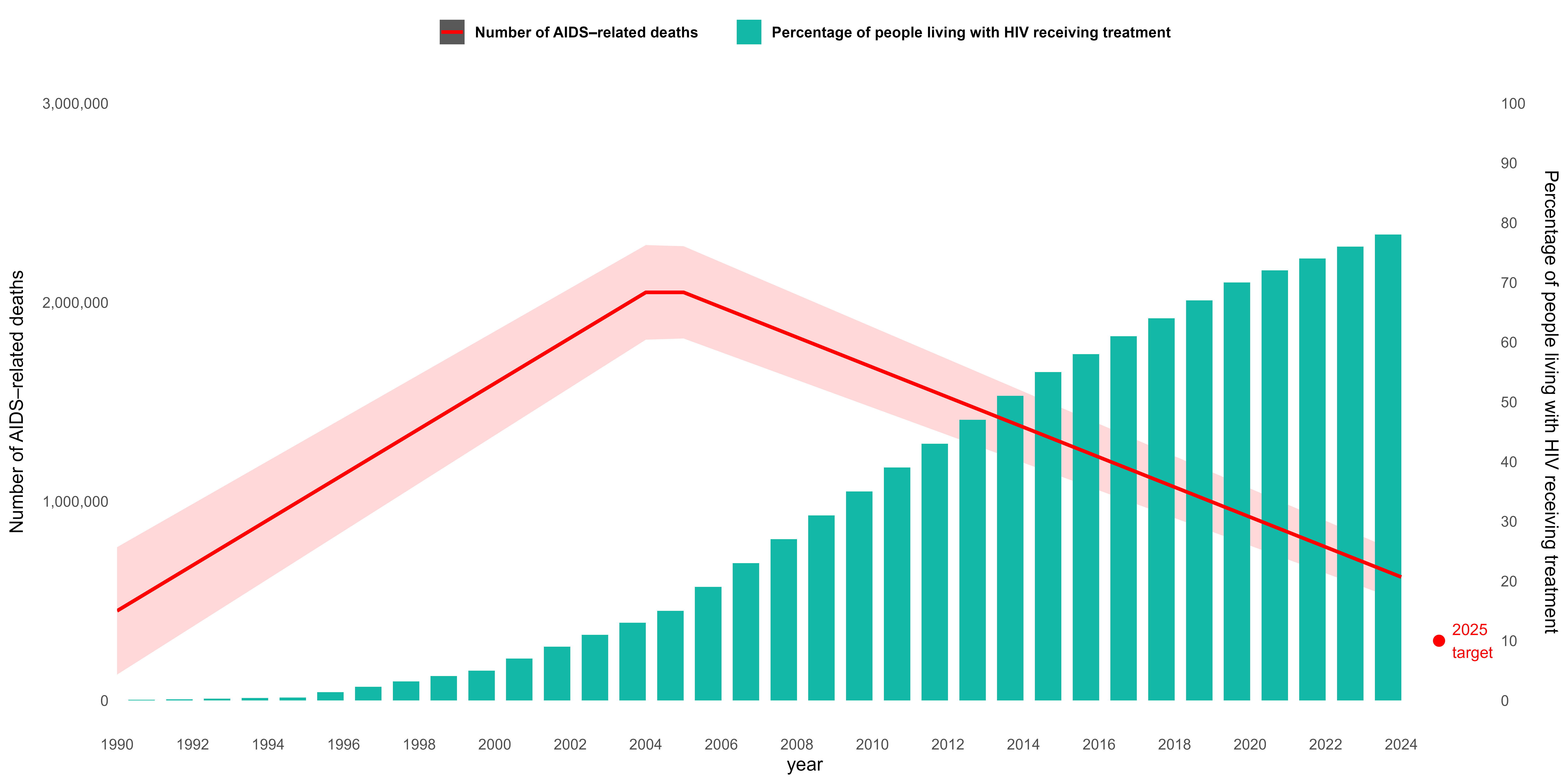

Looking back over three decades, long-term data reveal a striking shift: AIDS-related deaths peaked at more than 2 million annually in the early 2000s, but have since declined substantially, thanks to the scale-up of antiretroviral therapy (ART). The proportion of people with HIV receiving treatment has steadily increased, representing one of the most significant public health achievements of recent times. Yet, despite these gains, the world is not on track to meet the 2025 targets for universal treatment (red dot in the graph), reduced deaths, and the prevention of new infections.

AIDS related deaths, 2025 target and percentage of people living with HIV receiving treatment, globally 1990-2023

The State of HIV in 2025 assessment highlights several persistent challenges. First, the global community is not on course to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030, globally. Although progress has been made toward universal treatment access, substantial gaps remain. Prevention efforts are also lagging, with an inadequate scale-up of highly effective prevention tools such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), harm reduction programs, and innovative testing strategies. Moreover, the epidemic continues to be fueled by deep-rooted inequalities—both locally and globally—that limit access to healthcare, perpetuate stigma, and exacerbate vulnerabilities in marginalized populations.

Taken together, these trends paint a picture of both hope and warning. The world has demonstrated that large-scale progress against HIV is possible, but the next phase of the response requires renewed urgency, equity-driven strategies, and accelerated global commitment. Without addressing these systemic barriers, the vision of ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 will remain out of reach.

Advances in HIV Treatment2–6

The treatment of HIV in 2025 stands as one of the great successes of modern medicine, yet it continues to evolve to meet diverse patient needs. The guiding principle remains clear: treatment should be immediate, universal, and lifelong. With uninterrupted access to antiretroviral therapy (ART), people living with HIV can expect not only to live long and healthy lives but also to raise children without transmitting the virus and to maintain intimate partnerships safely, thanks to the transformative principle of U=U (Undetectable = Untransmissible).

The guiding principle: treatment should be immediate, universal, and lifelong

The Current Standard: Integrase Inhibitor–Based Regimens

The backbone of contemporary ART is the integrase inhibitor class, which now defines first-line therapy worldwide. Modern regimens combine two or three drugs into simple, once-daily, fixed-dose tablets that are highly effective, well tolerated, and have few drug interactions. Importantly, they offer a high barrier to resistance and can be taken safely for decades. Combinations such as:

Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide (BIC/FTC/TAF)

Tenofovir/Lamivudine/Dolutegravir (TLD)

Dolutegravir/Lamivudine (DTG/3TC)

are widely endorsed in both the DHHS (2024) and IAS–USA (2024) guidelines.

In addition, regimens containing tenofovir simultaneously address hepatitis B virus (HBV) co-infection, an important benefit in regions where both infections are common.

| Abbreviation | Full Name (Generic) | Class |

|---|---|---|

| 3TC | Lamivudine | NRTI (Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor) |

| ABC | Abacavir | NRTI |

| AZT / ZDV | Zidovudine | NRTI |

| FTC | Emtricitabine (Fluoro-Thia-Cytidine) | NRTI |

| TDF | Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | NRTI |

| TAF | Tenofovir alafenamide | NRTI |

| DTG | Dolutegravir | INSTI (Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor) |

| BIC | Bictegravir | INSTI |

| RAL | Raltegravir | INSTI |

| CAB | Cabotegravir | INSTI (long-acting injectable available) |

| EFV | Efavirenz | NNRTI (Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor) |

| NVP | Nevirapine | NNRTI |

| RPV | Rilpivirine | NNRTI |

| DRV | Darunavir | PI (Protease Inhibitor) |

| ATV | Atazanavir | PI |

| LPV/r | Lopinavir/ritonavir | PI (boosted with ritonavir) |

| RTV | Ritonavir | PI (used mostly as a booster) |

| COBI | Cobicistat | Pharmacokinetic booster (not antiviral by itself) |

Beyond “One Size Fits All”

Despite near-perfect single-pill regimens, challenges remain. Suboptimal adherence to daily oral therapy can lead to viral resistance, while some patients cannot reliably take pills due to social, medical, or psychological barriers. For such individuals, long-acting injectable ART represents a revolutionary alternative. By reducing the reliance on daily adherence, long-acting options improve convenience, help overcome stigma associated with pill-taking, and may reduce drug–drug interactions.

Long-Acting Injectables: CAB/RIL

A major breakthrough came with the FDA approval of cabotegravir (CAB, an integrase inhibitor) plus rilpivirine (RIL, an NNRTI), the first extended-release injectable ART. Given as two intramuscular injections every 1–2 months, CAB/RIL has proven non-inferior to oral therapy in clinical trials among virally suppressed patients.

Viral suppression

The amount of HIV in the blood (plasma HIV-1 RNA) is below the assay’s detection threshold—typically <50 copies/mL

While injection site reactions are the most common side effect, the regimen offers a critical option for those unable to maintain daily oral therapy. Failures can occur, however, sometimes leading to cross-class resistance.

Addressing Adherence Challenges

Recent clinical data highlight the promise of CAB/RIL for patients with viremia and adherence difficulties. In practice, long-acting ART has demonstrated high suppression rates—80% suppression with CAB/RIL and 92% with any regimen—even in populations historically considered hard to treat. Reflecting this, the DHHS guidelines (2024) now list CAB/RIL as an option for patients with adherence challenges, marking a genuine practice-changing moment in HIV care.

Injectable ART in Africa

The CARES study conducted in Kenya, Uganda, and South Africa showed that CAB/RIL is non-inferior to oral ART at 48 weeks (with 96-week data forthcoming), even in resource-limited settings where HIV monitoring and resistance testing are restricted. Although cases of resistance were observed, the study demonstrated that public health approaches using CAB/RIL are feasible in African contexts, provided that access barriers can be overcome.

Practical Considerations

CAB/RIL offers durable virologic suppression and improved quality of life, particularly for patients who are suppressed and switch from oral to injectable therapy. It can be life-saving for those unable to take oral ART. However, practical considerations remain: the regimen requires two intramuscular injections every two months, may cause pain and nodules at the injection site, and does not address HBV co-infection. In addition, CAB/RIL is expensive, difficult to manufacture, and not yet widely accessible in resource-limited settings. It is also not recommended during pregnancy, further underscoring the need for individualized treatment approaches.

On the Horizon

Looking ahead, innovation in long-acting therapies continues. Strategies under development include:

Longer-acting oral ART (once weekly or beyond)

Extended-duration injectables (every 6 months or longer)

Broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) combined with injectable ART

Subcutaneous implants capable of releasing ART over months or even years

These pipeline advances aim to further simplify HIV therapy, enhance adherence, and expand patient choice—moving closer to the goal of fully tailoring treatment to individual needs.

HIV Prevention7–9

Prevention remains the cornerstone of ending the HIV epidemic. Despite decades of progress, the global response continues to face gaps in scaling up effective prevention tools, particularly in regions with the highest burden of infection.

The Promise and Gaps of PrEP

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has emerged as one of the most powerful tools for preventing HIV. However, global uptake still lags far behind targets. According to Global AIDS Monitoring (2024), the number of people who have received PrEP at least once is well below the 2025 prevention goals, especially in regions such as Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East, where structural, economic, and cultural barriers hinder access.

Who is a PrEP candidate?

Current guidelines emphasize a broad eligibility framework: any sexually active individual with recent risk factors (partner with HIV, sexually transmitted infection within the past six months, or inconsistent condom use) qualifies. Additionally, people who inject drugs and anyone who asks for PrEP should be offered it, reflecting a shift toward patient-centered prevention.

Expanding PrEP Options

One of the strengths of PrEP lies in its diversity of delivery strategies. Options now include:

- Oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC): Taken daily.

- Tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (TAF/FTC): Taken daily.

- Long-acting injectable cabotegravir: Given every two months.

These choices allow PrEP to be tailored across populations, including cisgender men and women, transgender individuals, and people who inject drugs (PWID). For individuals with renal disease, injectable cabotegravir offers an alternative where oral regimens may be contraindicated.

PrEP options by population — Truvada®, Descovy®, and CAB-LA

| Population | TDF/FTC (Truvada®) Daily |

TAF/FTC (Descovy®) Daily† |

Cabotegravir (CAB-LA) Injection q2 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cis men | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Cis women | ✓ | —† | ✓ |

| Trans women | ✓ | (✓)† | ✓ |

| Trans men | ✓ | (✓)† | ✓ |

| PWID | ✓ | — | — |

| Renal disease | (✓)‡ | ✓ CrCl ≥ 30 |

✓ no renal adj. |

† Descovy® (TAF/FTC) PrEP indication excludes people at risk from receptive vaginal sex (insufficient efficacy data). Appropriate for anal exposure.

‡ Truvada® (TDF/FTC) generally avoid if CrCl < 60 mL/min; monitor renal function. Consider TAF/FTC (if anal exposure, CrCl ≥ 30) or CAB-LA when eGFR is reduced.

Note: CAB-LA approvals/data are for sexual transmission; limited evidence for parenteral exposure (PWID).

Lenacapavir: A New Frontier

The capsid inhibitor lenacapavir (LEN) has been hailed as a breakthrough in HIV prevention and treatment. With its unique mechanism blocking multiple steps of viral replication, lenacapavir can be administered as a subcutaneous depot injection lasting up to six months. Initially approved for salvage therapy in multidrug-resistant HIV, trials have now demonstrated its prevention potential.

For details, see my earlier Blog article: Lenacapavir: A Paradigm Shift in Long-Acting HIV Therapy and Prevention

The PURPOSE 1 and PURPOSE 2 trials, published in NEJM (2024), showed striking results:

- In PURPOSE 1: Zero HIV infections occurred in cisgender women receiving LEN

- In PURPOSE 2: LEN reduced incidence dramatically compared to background infection rates, with only two infections among nearly 2,000 participants.

While these results are groundbreaking, caveats remain. Injections can cause subcutaneous nodules and pain in up to 60% of participants, and widespread access in resource-limited settings will be critical if lenacapavir is to fulfill its prevention promise.

Choice Matters: The SEARCH Trial

Evidence from the SEARCH trial in Kenya and Uganda underscores the importance of offering people choices in HIV prevention. Participants randomized to a dynamic choice model—including PrEP, PEP, and injectable cabotegravir—achieved 70% prevention coverage versus only 13% under standard care, with no new HIV infections in the dynamic choice arm. This highlights that expanding the prevention toolbox and empowering people to select what works best for them is key to effective HIV control.

The Future of HIV Prevention

Looking ahead, prevention strategies are rapidly evolving beyond daily pills:

Lenacapavir: once-yearly injections under study.

Cabotegravir: extended to every four months, with implantable options in development.

Monoclonal antibodies: providing passive immunity.

Monthly oral pills (e.g.,MK-8527).

Novel delivery systems such as microarray patches and rectal douches/inserts.

MK-8527: An investigational once-monthly, oral nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor (NRTTI) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).It is in Phase-3 clinical trial (NCT 07044297)

Adherence remains a major barrier for oral PrEP in many populations, but long-acting PrEP has the potential to be a true game changer—if it can be made accessible to those most in need. To succeed, PrEP must become fully integrated into mainstream sexual health services, much like contraception and STI testing. Ensuring equitable access will be critical if the world is to leverage these advances and move closer to ending HIV as a global public health threat.

HIV Cure10–13

For decades, the idea of curing HIV remained out of reach. Yet today, scientific progress has moved the concept from impossibility to a growing reality. While no scalable cure exists yet, several remarkable milestones highlight how far the field has come and the innovative strategies now under development.

Stem Cell Transplants: The First Functional Cures

The first true HIV cures came through allogeneic stem cell transplantation in individuals who required treatment for hematologic malignancies. This strategy, while not scalable for the broader HIV population, provided proof of concept that eliminating the virus is possible.

Timothy Brown (Berlin Patient, 2009) was the first person cured of HIV through a stem cell transplant from a donor with the CCR5-Δ32 mutation, which makes cells resistant to HIV infection.

Adam Castillejo (London Patient, 2019) and others soon followed, including cases in New York (2021), Düsseldorf (2021), California (City of Hope, 2022), Geneva (2023), and most recently, another Berlin patient in 2024.

In total, at least seven people have now been cured through this approach, solidifying the principle that eliminating viral reservoirs is achievable.

HIV Remission Without Therapy

In parallel, researchers have identified rare individuals capable of controlling HIV in the absence of ongoing therapy—a state often called “functional cure” or “remission.”. These include:

- Elite controllers: Long-term non-progressors who naturally suppress HIV without ART.

- Post-treatment controllers: Patients, such as those in the French VISCONTI cohort, who maintain control after early ART interruption.

- Exceptional cases of natural control, suggesting that host immune responses, particularly CD8+ T cells, play a pivotal role in long-term viral suppression.

These insights highlight that a combination of low viral reservoirs and a sustained immune response are central to achieving remission.

The Landscape of Cure Research

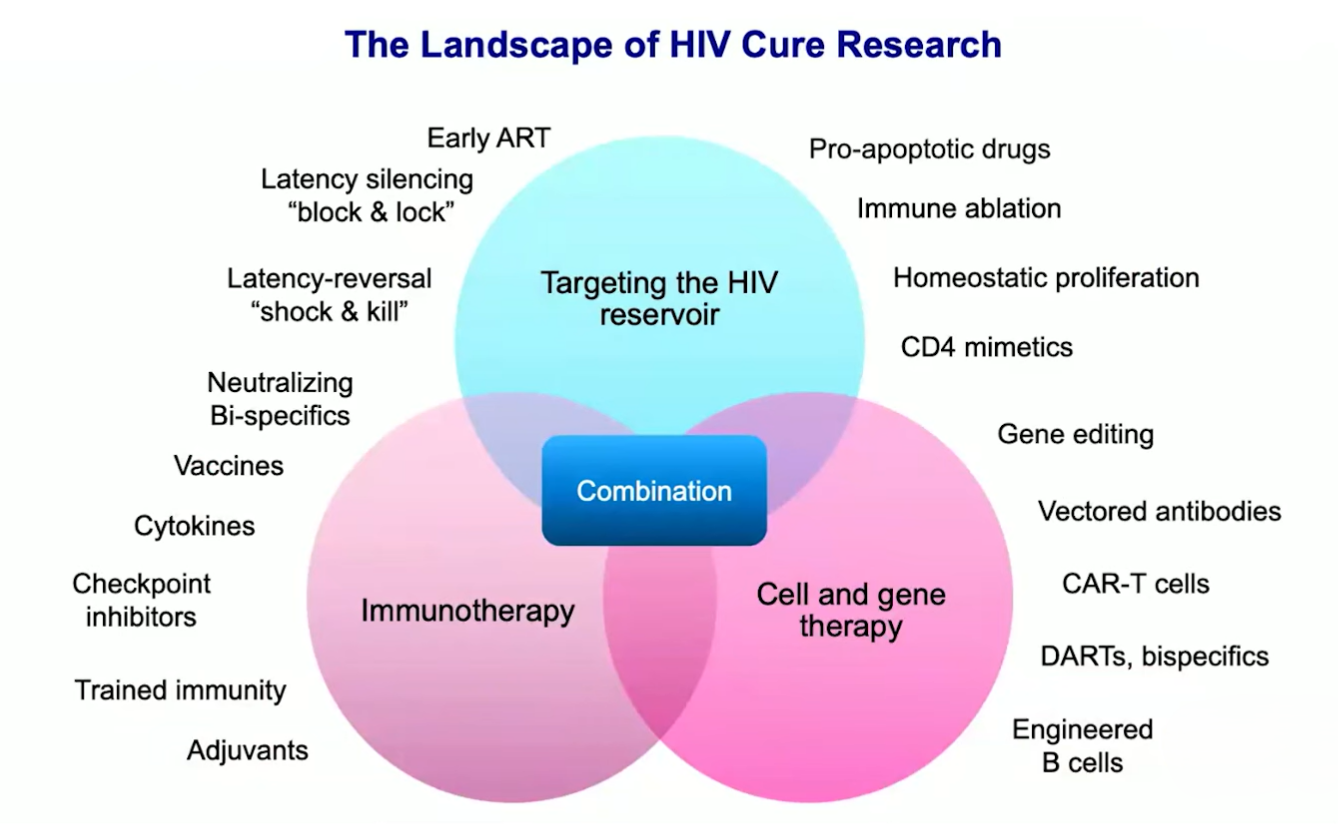

Cure research today spans three major domains, often pursued in combination strategies as shown in illustration below.

HIV cure Research strategies

| 1) Targeting the viral reservoir Reservoir |

|

| 2) Immunotherapy Immune |

|

| 3) Cell & gene therapy Cell/Gene |

|

HIV latency:

After infection, HIV hides its DNA (provirus) inside long-lived cells—mostly resting memory CD4⁺ T cells—where it’s transcriptionally silent (no virus made) but can wake up later. This hidden “reservoir” is why HIV rebounds if ART stops.

Latency silencing (“block & lock”):

Keep the provirus permanently OFF—using drugs or gene tools that shut down HIV transcription—so virus can’t rebound even off ART.

Latency reversal (“shock & kill”):

Turn latent virus ON with latency-reversing agents so infected cells reveal themselves (“shock”), then eliminate them with immune/antibody or cell-based killing (“kill”).

HIV Cure

1) Shock & Kill

Wake hidden HIV, then clear those cells.

Wake-up / shock nudges (LRAs):

- HDAC inhibitors – vorinostat, panobinostat, romidepsin

- PKC agonists – bryostatin-1, prostratin, ingenol derivatives

- TLR agonists – TLR7 (vesatolimod), TLR9 (lefitolimod), TLR8 (selgantolimod)

Kill (clear the reactivated cells):

- Therapeutic vaccines

- Broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs)

- Cell therapies – CAR-T

2) Block & Lock

Keep HIV’s “on switch” off for good.

- Tat blockers

- CRISPR-based “mute switch”

- Re-shelving HIV in quieter DNA

Early Results from Combination Approaches

Promising results are emerging from early trials combining these approaches. For example, the UCSF amfAR Combination Study tested a three-stage regimen combining therapeutic vaccination, immune modulation (TLR9 agonist), and broadly neutralizing antibodies. Among 10 participants, 7 achieved sustained control (~1000 copies/mL or less) after ART interruption, with one showing no viral rebound.

These findings suggest that while no single intervention is likely to achieve a cure, carefully designed combinations may progressively push the field closer to scalable remission strategies.

State of HIV Cure

As of 2025, the message is clear: HIV can be cured—but only in a handful of people so far. Post-treatment control remains possible for some, but it is still the exception rather than the rule. Current experimental interventions are intensive, expensive, and not widely scalable, and even in cases of remission, careful monitoring is required due to the risk of viral rebound. The future direction of the field is shifting toward the idea of a “one-shot cure”—a globally scalable approach leveraging gene-editing technologies (such as CRISPR delivered via viral vectors like AAV-9) or advanced cell-based therapies like CAR-T cells. These innovations hold promise for a durable, widely accessible cure, but remain in early clinical stages.

In short, while the cure for HIV is no longer theoretical, transforming it into a safe, scalable, and global solution remains one of the greatest scientific and public health challenges of our time.

Conclusion

HIV science in 2025 stands at a crossroads—treatment is effective, prevention tools are expanding, and cure research is accelerating. Yet global equity, access, and scalability remain the decisive challenges ahead.