Depression and Its Pharmacology1–3

Depression encompasses a range of unipolar and bipolar mood disorders that affect approximately 280 million people worldwide. Neurobiological underpinnings include monoaminergic imbalance, neuroinflammation, HPA axis dysregulation, and impaired neurocircuitry. Clinically, accurate subtype identification is critical for optimal treatment selection—particularly distinguishing MDD from bipolar depression, or recognizing features of atypical or psychotic depression. While SSRIs remain first-line for many, emerging therapies such as esketamine and digital CBT are expanding the treatment landscape. A biopsychosocial model remains the cornerstone of care.

Types of Depression

| Type of Depression | Key Features |

|---|---|

| Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) | ≥2 weeks of low mood, anhedonia, fatigue, changes in sleep/appetite |

| Persistent Depressive Disorder | Chronic symptoms for ≥2 years, often milder but long-lasting |

| Bipolar Depression | Occurs within bipolar disorder, alternating with mania/hypomania |

| Postpartum Depression | Begins after childbirth; includes sadness, guilt, bonding issues |

| Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) | Seasonal onset (usually winter), linked to lack of sunlight |

| Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder | Severe emotional and physical symptoms before menstruation |

| Psychotic Depression | Includes delusions or hallucinations with depressive themes |

| Atypical Depression | Mood improves with positive events; increased sleep and appetite |

| Situational/Reactive Depression | Triggered by life stressors; may evolve into clinical depression |

| Depression in Medical Illness | Associated with chronic physical illness; complex treatment needs |

The mainstream pharmacological treatment approach targets monoaminergic pathways, especially serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine (NE), and dopamine (DA), using agents such as SSRIs (e.g., sertraline, fluoxetine), SNRIs, tricyclics and tetracyclic antidepressant.

Clinical guidance in following Tables below are compiled from multiple expert sources including AMH, Maudsley Guidelines, NICE, and TG Australia5

Antidepressants and Their Dosing in Older Adults

| Antidepressant | Therapy Line | Initiation Dose | Maintenance Dose | Maximum Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram | First-line | 10 mg | 10–20 mg | 20 mg |

| Escitalopram | First-line | 5 mg | 5–10 mg | 10 mg |

| Sertraline | First-line | 25–50 mg | 50–100 mg | 100 mg (occasionally 150 mg) |

| Mirtazapine | First-line | 15 mg | 15–30 mg | 45 mg |

| Fluoxetine | Second-line | 20 mg | 20 mg | 40–60 mg |

| Venlafaxine | Second-line | 37.5 mg | 75–150 mg XR | 150–225 mg XR |

| Duloxetine | Second-line | 30 mg | 60 mg | 120 mg |

| Vortioxetine | Second-line | 5–10 mg | 5–20 mg | 20 mg |

| Agomelatine | Second-line | 25 mg | 25–50 mg | 50 mg |

| Fluvoxamine | Third-line | 50 mg | 100–300 mg | 300 mg/day |

| Paroxetine (Use with caution) | Third-line | 20 mg | 20–50 mg | 50 mg |

| Desvenlafaxine | Third-line | 50 mg | 50–150 mg | 200 mg |

| Amitriptyline | Third-line | 50 mg | 50–100 mg | 150 mg |

| Nortriptyline | Third-line | 10–25 mg | 50–75 mg | 100 mg |

Comparison of Antidepressant Classes in Older Adults

| Drug Class | Effectiveness | Tolerability | Safety Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) | First-line in older adults; avoid fluoxetine and paroxetine | Better tolerated than SNRIs and TCAs | ↑ GI bleeding risk, ↑ fall/fracture risk, serotonin toxicity |

| Serotonin and Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) | Similar efficacy to SSRIs and mirtazapine | Less tolerated than SSRIs but better than TCAs | All SSRI risks plus ↑ BP, palpitations, tachycardia; caution in cardiovascular disease |

| Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) | Reserved for treatment-resistant or melancholic depression | Least tolerated among the three in older adults | ↑ Fall/fracture risk, cognitive impairment due to anticholinergic effects |

The following tables clearly present the adverse effects of antidepressants, categorized by high, moderate, and low incidence rates.

High (+++) Adverse Effects

| Antidepressant | High (+++) Adverse Effects | Severity |

|---|---|---|

| First-line Agents | High (+++) | |

| Citalopram | Hyponatraemia, Sexual Dysfunction | High (+++) |

| Escitalopram | Hyponatraemia, Sexual Dysfunction | High (+++) |

| Sertraline | Hyponatraemia, Sexual Dysfunction | High (+++) |

| Mirtazapine | Sedation, Weight Gain, Withdrawal | High (+++) |

| Second-line Agents | High (+++) | |

| Fluoxetine | Hyponatraemia, Sexual Dysfunction | High (+++) |

| Duloxetine | Hyponatraemia, Withdrawal | High (+++) |

| Venlafaxine | Hyponatraemia, Nausea/Vomiting, Sexual Dysfunction, Withdrawal | High (+++) |

| Third-line Agents | High (+++) | |

| Fluvoxamine | Hyponatraemia, Nausea/Vomiting, Sexual Dysfunction | High (+++) |

| Paroxetine | Hyponatraemia, Sexual Dysfunction, Withdrawal | High (+++) |

| Desvenlafaxine | Cardiac Conduction, Sedation, Weight Gain, Withdrawal | High (+++) |

| Amitriptyline | Anticholinergic Effects, Cardiac Conduction, Postural Hypotension, Sedation, Sexual Dysfunction, Weight Gain | High (+++) |

Moderate (++) Adverse Effects

| Antidepressant | Moderate (++) Adverse Effects | Severity |

|---|---|---|

| First-line Agents | Moderate (++) | |

| Citalopram | Nausea/Vomiting, Weight Gain, Withdrawal | Moderate (++) |

| Escitalopram | Nausea/Vomiting, Weight Gain, Withdrawal | Moderate (++) |

| Sertraline | Nausea/Vomiting, Withdrawal | Moderate (++) |

| Second-line Agents | Moderate (++) | |

| Fluoxetine | Nausea/Vomiting, Withdrawal | Moderate (++) |

| Duloxetine | Nausea/Vomiting, Sexual Dysfunction | Moderate (++) |

| Vortioxetine | Hyponatraemia | Moderate (++) |

| Third-line Agents | Moderate (++) | |

| Fluvoxamine | Withdrawal | Moderate (++) |

| Paroxetine | Nausea/Vomiting, Weight Gain | Moderate (++) |

| Amitriptyline | Hyponatraemia, Withdrawal | Moderate (++) |

| Nortriptyline | Cardiac Conduction, Hyponatraemia, Postural Hypotension, Withdrawal | Moderate (++) |

Low (+) Adverse Effects

| Antidepressant | Low (+) Adverse Effects | Severity |

|---|---|---|

| First-line Agents | Low (+) | |

| Citalopram | Cardiac Conduction | Low (+) |

| Escitalopram | Cardiac Conduction | Low (+) |

| Sertraline | Weight Gain | Low (+) |

| Mirtazapine | Anticholinergic Effects, Hyponatraemia, Nausea/Vomiting, Postural Hypotension | Low (+) |

| Second-line Agents | Low (+) | |

| Fluoxetine | Cardiac Conduction, Weight Gain | Low (+) |

| Duloxetine | Postural Hypotension, Weight Gain | Low (+) |

| Venlafaxine | Cardiac Conduction, Postural Hypotension, Sedation, Weight Gain | Low (+) |

| Agomelatine | Hyponatraemia, Sedation | Low (+) |

| Vortioxetine | Cardiac Conduction, Nausea/Vomiting, Sedation, Weight Gain, Withdrawal | Low (+) |

| Third-line Agents | Low (+) | |

| Fluvoxamine | Sedation, Weight Gain | Low (+) |

| Paroxetine | Anticholinergic Effects, Sedation | Low (+) |

| Desvenlafaxine | Anticholinergic Effects, Hyponatraemia, Nausea/Vomiting, Postural Hypotension | Low (+) |

| Amitriptyline | Nausea/Vomiting | Low (+) |

| Nortriptyline | Anticholinergic Effects, Nausea/Vomiting, Sedation, Sexual Dysfunction, Weight Gain | Low (+) |

Pharmacodynamic Overview

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) exert their antidepressant effect primarily by selectively inhibiting the serotonin transporter (SERT), thereby increasing synaptic concentrations of serotonin (5-HT) with minimal activity at other receptor sites.

In contrast, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) inhibit both SERT and the norepinephrine transporter (NET), enhancing synaptic levels of 5-HT and norepinephrine (NE), though with varying affinity (e.g., venlafaxine is more serotonergic at lower doses).

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) also inhibit SERT and NET, but unlike SSRIs/SNRIs, they non-selectively antagonize multiple receptors, including muscarinic cholinergic (M1), histamine H1, and α1-adrenergic receptors, contributing to their anticholinergic, sedative, and orthostatic side effect profiles.

Tetracyclic antidepressants, such as mirtazapine, uniquely antagonize presynaptic α2-adrenergic autoreceptors and heteroreceptors, leading to increased NE and 5-HT release, and also block 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors, which may enhance anxiolytic and antiemetic effects. Additionally, its potent H1 histamine receptor antagonism contributes to its sedative and appetite-stimulating properties.

While these medications have demonstrated benefit in moderate to severe cases, they are often prescribed for mild depression, grief reactions, or stress-related symptoms — domains where their efficacy is limited or absent.

The Current State: Over prescription and Long-Term Use

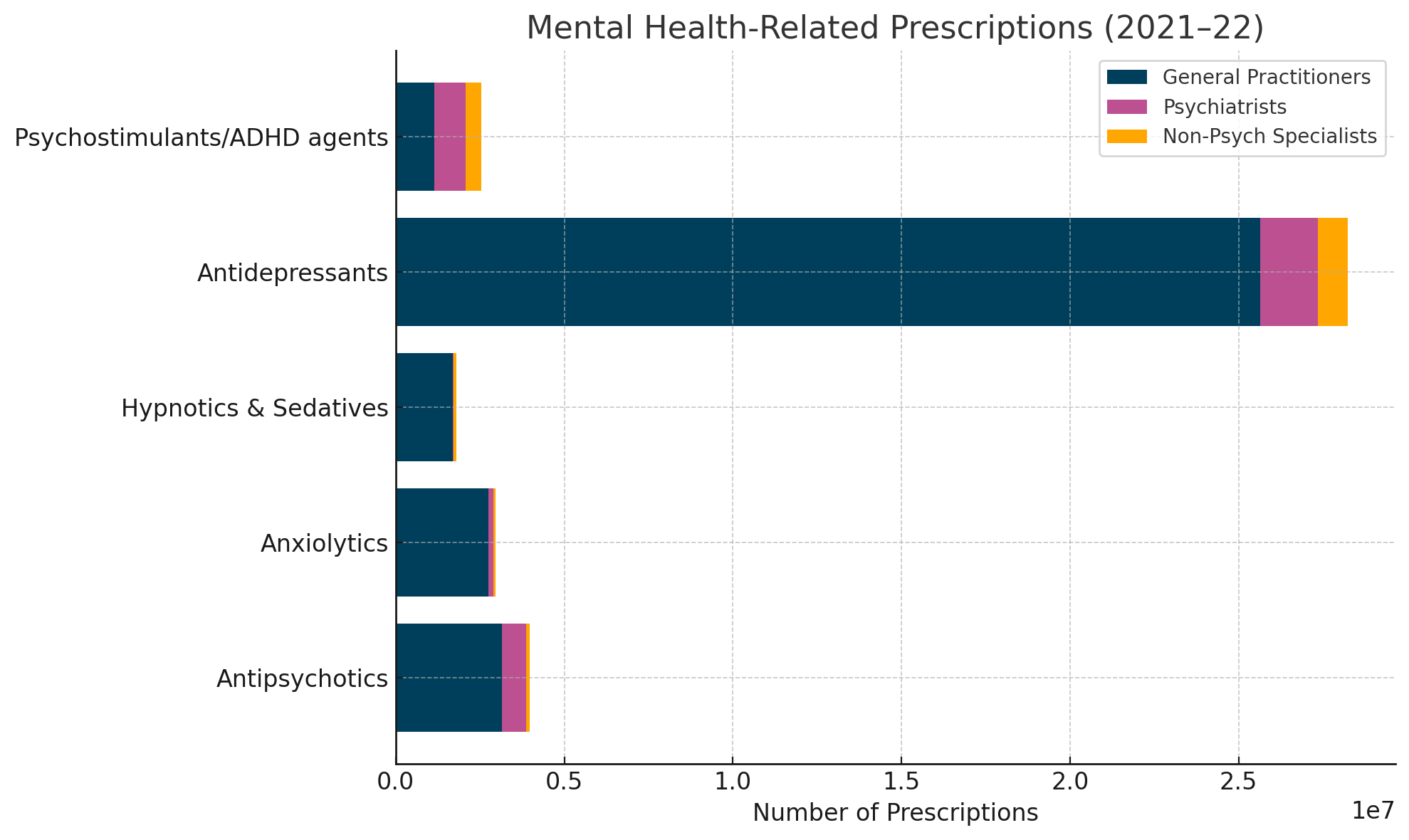

In Australia, general practitioners (GPs) are responsible for 92% of antidepressant prescriptions, often continuing treatment beyond the evidence-based duration. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, over 25 million antidepressant prescriptions were dispensed in 2021–2022 alone6

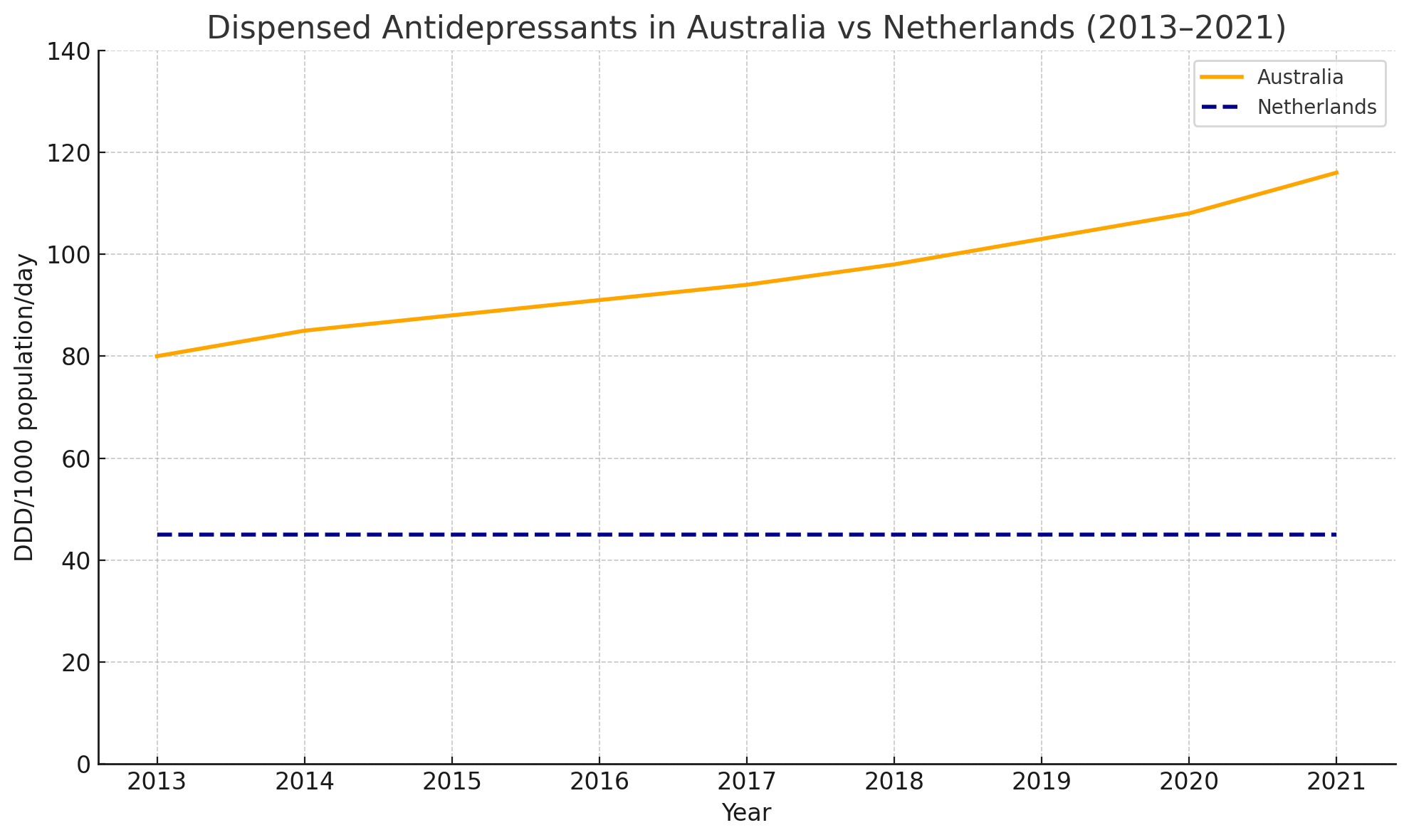

Similarly the antidepressant consumption (defined daily dose per 1,000 people per day) across OECD countries in the years 2000 vs 2019 has also been increased7

Long-term use is increasing disproportionately in Australia compared to other nations like the Netherlands: Two medications in particular — sertraline and escitalopram — have surged into Australia’s top 10 most prescribed drugs by defined daily doses (DDD)8

Top 10 PBS and RPBS Drugs by DDD/1000 Population/Day (Australia, 2022–2023)9

| Rank | Drug | DDD/1000 pop/day |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Atorvastatin | 80.72 |

| 2 | Rosuvastatin | 77.95 |

| 3 | Amlodipine | 57.81 |

| 4 | Perindopril | 56.60 |

| 5 | Telmisartan | 36.14 |

| 6 | Candesartan | 36.13 |

| 7 | Sertraline | 30.11 |

| 8 | Escitalopram | 28.31 |

| 9 | Metformin | 28.25 |

| 10 | Irbesartan | 27.66 |

Yet despite this rise, there is growing concern over unwarranted variation in prescribing, with increased rates seen in:

Older adults (≥65 years; double the rates)

Women (1.5x more likely)

Lower socioeconomic and inner regional communities

The “WHY” of Deprescribing and Challenges10–13

Why Deprescribing Matters

“Long-term use is not harmless, nor is it always helpful.”

The Productivity Commission on Mental Health emphasized the urgency to reform psychotropic prescribing, citing antidepressants as a major concern due to their frequency and adverse outcomes in aged care and community settings:

The case for deprescribing is clear:

Many patients are maintained on antidepressants despite remission.

Withdrawal is common, sometimes severe.

Depression is not a chronic, lifelong disorder in all cases.

Long-term pharmacological maintenance lacks strong benefit evidence for many.

Why Don’t People Stop Antidepressant

Patient say:

- Expect their doctor would suggest stopping if it were warranted

- Unpleasant withdrawal symptoms

- Fear of relapse

Doctor say:

- Reluctant to ‘rock the boat’ & destabilise a stable situation

- Time constraints

- Patient fear of relapse

- Lack of tapering guidance

- Poor access to non-pharmaceutical alternatives

Recognizing the Difference: Relapse vs. Withdrawal

One of the most critical challenges in antidepressant deprescribing is accurately distinguishing between relapse of the underlying condition and withdrawal symptoms that emerge after dose reduction or discontinuation. Misinterpreting withdrawal for relapse may lead to unnecessary reinstatement of antidepressants, prolonging treatment and reinforcing patient dependency.

To navigate this clinical gray zone, it is essential to understand three commonly used assessment tools:

PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire-9)

A validated screening tool for depression that assesses the frequency of symptoms such as low energy, sleep disturbances, and anhedonia over the past two weeks. It is frequently used in both primary care and psychiatric settings to monitor depressive symptom severity.GAD-7 (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7)

A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety symptoms. It captures psychological (e.g., nervousness, irritability) and somatic (e.g. restlessness, muscle tension) components of anxiety.DESS (Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms)

A structured checklist specifically developed to identify withdrawal symptoms after cessation of serotonergic antidepressants. Common items include dizziness, nausea, agitation, and sensory disturbances.Why this Confusion Happens

Symptom Overlap: PHQ-9 (Depression), GAD-7 (Anxiety),and DESS (Withdrawal)

| PHQ-9 (Depression) | GAD-7 (Anxiety) | DESS (Withdrawal) |

|---|---|---|

| “Feeling tired or having little energy” | “Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge” | ‘Anxiety/nervousness’ |

| “Being fidgety or restless” | “Becoming easily annoyed or irritated” | ‘Irritability’ |

| “Trouble falling or staying asleep” | – | ‘Fatigue’, ‘agitation’, ‘insomnia’ |

These symptom overlaps are deceptive. For example, a patient experiencing restlessness and insomnia after tapering an SSRI may be exhibiting serotonergic withdrawal, not a depressive or anxiety relapse. If misinterpreted, clinicians may mistakenly reinitiate or increase antidepressant therapy, thus reinforcing long-term use and missing the opportunity for successful deprescribing.

The Clinical Imperative

To avoid this pitfall:

Clinicians must time symptoms in relation to dose reduction—withdrawal symptoms often arise within days to weeks after tapering, while true relapse generally has a slower onset.

Utilize the DESS checklist to screen for discontinuation-related phenomena.

Provide psychoeducation to patients so they understand the nature of withdrawal and can anticipate and report these symptoms accurately.

Understanding this distinction supports safe and effective tapering, reinforces patient trust, and contributes to reducing unwarranted long-term antidepressant use.

Why Stops Antidepressants

Health & quality of life benefits

More energy & motivation

Improved weight control

Decreased polypharmacy & risk of falls

Improved sexual functioning (sexual adverse effects can be long-lasting)

Increased ability to feel joy, love, excitement, & care for others

Free of dependence on medication

Financial benefits (medical & prescriptions)

Hyperbolic Tapering: The Gold Standard

Unlike traditional “linear” dose reductions, hyperbolic tapering considers the pharmacodynamics of antidepressants — particularly the non-linear relationship between dose and receptor occupancy.

Why It Works

- Reduces neurobiological shock during withdrawal

- Minimizes rebound symptoms

- Allows time for receptor and neurochemical adaptation

Protocol Highlights:

Stepwise, individualized taper

Slower reductions at lower doses (e.g., tapering 1.25 → 1.0 → 0.5 → 0.25 mg)

Use of liquid formulations for precision

Patient engagement and psychoeducation throughout

To prompt and support safe cessation of long-term antidepressants the best intervention out there is the RELEASE 3As brief intervention. Click to view

RELEASE 3As: Ask, Advise, Assist

Ask

- How long have you been taking antidepressants?

- Have you ever tried to stop?

Advise

- Not harmless (emotional numbing, sexual dysfunction, lethargy & fatigue, weight gain, falls)

- Not recommended (Clinical guidelines: 6–12 months therapy for a single episode)

- Not a long-term condition caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain

- Withdrawal symptoms are common, can be severe & are not relapse

Assist

- Hyperbolic tapering protocol (step-by-step guidance for decreasing drug dose)

- Mini doses

Lets explore case study to see the implication of 3As intervention

Case Study: Antidepressant Deprescribing in an Older Adult

Patient Profile:

A 70-year-old woman presents with a history of overweight, type 2 diabetes, hypertension (HT), and osteoarthritis (OA). She has been a widow for 15 years, lives alone, and reports low physical activity due to lethargy and joint pain. She denies any formal psychiatric follow-up over the past decade.

Current Medications:

Statin for dyslipidemia

ACE inhibitor for hypertension

Metformin for diabetes

Paracetamol for osteoarthritic pain

Sertraline 100 mg, taken continuously for 15 years

Application of the RELEASE 3As Brief Intervention

Ask

Duration of antidepressant use: 15 years

Previous attempts to discontinue: None

Advise

Long-term antidepressant use is not harmless: associated with emotional blunting, sexual dysfunction, weight gain, and falls, especially in older adults.

Continued use is not clinically recommended for a single depressive episode—guidelines suggest 6–12 months of treatment followed by reassessment.

Depression is not a chronic condition resulting from a permanent chemical imbalance.

Withdrawal symptoms may occur upon discontinuation, but are transient and not indicative of relapse.

Assist

Initiate a hyperbolic tapering protocol, gradually reducing the sertraline dose using mini-doses over several months.

Monitor symptoms using tools such as the DESS checklist to differentiate withdrawal from relapse.

Provide support with non-pharmacological strategies, including behavioral activation and social support networks

click to view clinical guide to antidepressant deprescribing for more details..

Clinical Guide to Antidepressant Deprescribing

Deprescribing Triggers

- No current indication for continued use

- Dose exceeds standard recommendations

- Harms outweigh potential benefits

- Patient preference

General Deprescribing Protocol

- Taper slowly, with an individualized plan

- Initial suggestion: Reduce current dose by 25% every 1–4 weeks

- Monitor symptoms every 1–2 weeks

- Adjust tapering based on patient’s tolerance

-

Use slower schedules for:

- Long-term users

- High-dose patients

- History of withdrawal symptoms

Tools: The RELEASE trial from the University of Queensland provides tapering guides for 15 antidepressants at 3 rates (fast, slow, very slow).

📄 View Full PDF 📄 View Full PDF 📄 View Full PDF

Pharmacy role: Pharmacists can compound mini-doses for accurate tapering.

Withdrawal Symptoms

- Physical: Fatigue, headache, sweating, dizziness, nausea, “brain zaps”

- Psychological: Anxiety, agitation, insomnia, irritability

- May mimic relapse, but differ in timing and pattern

Withdrawal vs. Relapse

| Withdrawal | Relapse |

|---|---|

| Hours–days onset | Weeks–months onset |

| Symptoms resolve with reinstatement | Slow symptom resolution |

| Physical + psychological | Mostly psychological |

| Wave-like pattern | Persistent pattern |

Withdrawal Risk by Drug

- Highest Risk: desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, mirtazapine, moclobemide, paroxetine, venlafaxine

- Moderate Risk: citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, TCAs

- Low Risk: vortioxetine, dosulepin

- Lowest Risk: agomelatine

If Withdrawal Occurs

- Slow the taper

- Reduce the decrement step

- Pause taper temporarily

- Revert to previous dose, then restart slower

Patient Support Essentials

- Educate on risks/benefits of stopping

- Share symptom tracking tools (e.g., DESS)

- Offer access to psychological and lifestyle interventions

- Regular review & reassurance

Conclusion: Deprescribing is Completion, Not Neglect

Antidepressant deprescribing must be reframed as a proactive clinical strategy — not an act of abandonment. When guided by evidence, implemented with empathy, and structured through protocols like hyperbolic tapering, it empowers recovery, restores autonomy, and reduces long-term harm.

In the evolving landscape of mental health care, deprescribing represents the thoughtful closing chapter of pharmacological treatment.